|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

|

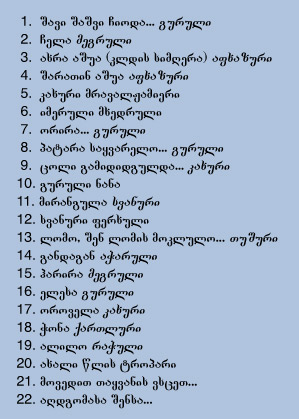

1. Shavi shashvi chioda..., table song - 2:21

2. Tchela, waggoner's song - 3:09

3. Akhra ashua - 2:03

4. Sharatin ashua, ring dance - 1:49

5. Mravalzhamieri, table song - 4:30

6. Mkhedruli, horsemen' song - 1:51

7. Orira, warriors' song - 2:23

8. P'at'ara saqvarelo..., table song - 4:10

9. Tsoli gamididgulda... - 2:03

10. Guruli Nana, cradle song - 2:11

11. Mirangula - 5:26

12. Perkhuli, ring dance - 4:41

13. Lomo shen lomis mok'lulo... - 2:57

14. Gandagan, dance tune - 2:06

15. Harira, ring dance - 3:30

16. Elesa, work song - 2:03

17. Orovela, ploughman's song - 4:22

18. Tch'ona, Easter song - 3:56

19. Alilo, Christmas song - 4:26

20. Tropar of New Year - 2:41

21. Movedit taqvanis vstset... - 2:18

22. Tropar of Easter - 1:10

|

|

A highly developed, orally transmitted tradition of part-singing is to be found in Georgia. Part-singing here is not the result of any arrangement for the concert stage, rather is integral to the fabric of this music, where resulting harmonies are often more important than the constantly weaving melodic lines. Today this vocal tradition is kept alive mainly by inhabitants of rural areas. For the past hundred years, though, it could also be heard in concert: the first performing group was established in 1885 and by 1907, recordings were already being made. Ensemble Georgika, founded in 1989 is, among many such groups presently performing in Georgia, one of the youngest, and after 70 years of Soviet rule, one of the first to survive without state support and patronage. Its 14 singers and 3 instrumentalists wish not only to continue the existing concert tradition, but based on archive recordings and instruction from authoritative village elders, also strive to preserve its diversity and vivacity. A highly developed, orally transmitted tradition of part-singing is to be found in Georgia. Part-singing here is not the result of any arrangement for the concert stage, rather is integral to the fabric of this music, where resulting harmonies are often more important than the constantly weaving melodic lines.

With this, their third CD (vol.I: FM 50011, vol.II FM 50013), Ensemble Georgika takes the listener on an imaginary journey through the vastly different Georgian landscapes existing between the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea. 22 songs from 10 of the 16 historic-ethnographic regions offer, aside from their musical diversity and originality, a glimpse into a rich culture and turbulent history continually touched by tragedy.

A richly laden table, around which friends and guests are gathered, is now, as in the past, the place where traditional song in Georgia flourishes at its best. According to Caucasian drinking custom, where one is allowed to drink only after having made the acquaintance of all present, it is the toasting, which challenges one to ever greater rhetorical and musical flights of fancy. These toasts, for whose themes a chosen Tamada is responsible, alternate with song steeped in centuries-old improvisational traditions. The art of polyphonic part-singing in Guria, where all 3 soloists enjoy equal artistic freedom, has not been surpassed elsewhere. To the bass voice goes the difficult task of ensuring harmonic coherence (see also 8; vol.I: 8; vol. II:1).

1. Shavi shashvi chloda... Guria, table song

(Davit Shanidze, Archil and Malkhaz Ushveridze, soli.)

|

| Hospitality is not only the ability to spread contentment among guests, it also obliges to solidarity in time of need, and support for those embarking on risky undertakings. One of the most popular of these challenges is hunting; its inherent dangers are sung of in other songs on this CD (see 3, 12). |

"The black thrush wailed, / the oldest one, the leader. / The mountains are covered with snow, / nowhere a passable way. / To the chase, barking, my Mura, / there is much game hither."

|

2. Tchela, Samegrelo, waggoner's song

|

Our travels begin on the Araba, a two-wheeled cart pulled by 2 oxen or buffalo, by Tchela, as they are called in Samegrelo if they have a white spot, and Busk'a, "the greedy one". Hi the driver (D. Shanidze) calls to them if the Araba threatens to jump the tracks. If he lamented their destiny as slaves under the yoke and reproached their laziness in the same-named instrumentally accompanied song (see vol. I;2), this time he is up to jesting: "ch'uri" (the earthen wine-barrel lying in the back of the cart), and "nabadare" (a fungus the oxen like?) are, Tchela, your high school. What do you want to study for, chew your cud and be content." Yet he himself has nothing to laugh about: "Grief has emaciated me, poor am I, a rich man made my dearly beloved his wife." The images and the, for Georgian songs, rather rare use of social themes, suggest that the origins of this text lie in the 19th century. At that time abrupt changes due to the Russian occupation heightened social differences in Georgia.

|

Georgian has been a written language since the 3rd century. As a literary and ecclesiastical language, until the Russian occupation at the beginning of the 19th century, it had in Svaneti and Samegrelo, where Georgian-related languages are in use, and in Abchasia, a role similar to medieval Latin in Western Europe. For the Abchasians, who belong to the West Caucasian branch of the Caucasus-language group, a script of their own based on the Russian alphabet, has in the meantime been created by Soviet philologists. The music of the Abchasians, or Apsua, as they call themselves, constitutes a peculiar type of Caucasian part-singing, even if, due to close contact among the overlapping settlements in Abchasia, similarities to Svanetian and Megrelian music exist. A basic difference, for example, can be seen in the cadences at the end of the verses: in the Megrelian Tchela (2) and the Svanetian Mirangula (11) the bass line ascends stepwise to join the other two voices in a common final tone, in the following Abchasian song it descends suddenly.

|

3. Akhra ashua, Abkhazeti

|

A hunter following a 6-pointed stag starts up a steep mountain, from which he is unable to descend once it becomes dark. So that he will not fall asleep and inadvertently slide down the mountainside, his brother sings him racy and impudent songs, some even making fun of him, in an attempt to keep him awake. The hunter, not seeing the humor in the situation, kills his brother the next day for the insolences which actually saved his life. When insight into his brother's provocations dawns, he takes his own life.

|

| 4. Sharatin ashua, Abkhazeti, circle dance |

| For the circle dance the singers position themselves in a circle, which begins to rotate during the singing. The ritualistic character of this primeval dance is also mirrored in mythological texts from the high mountain regions of Caucasus (see 12), but in the valleys, it is often hidden in apparently nonsensical banter, contributed by the dancer in the center of the circle: |

"All the streams are dry, / without even a drop of water remaining. / The alder, upon which the vines are creeping, / also gives no wine."

|

The version of this song presented by Georgika was handed-down by the Megrelian singer Nok'o Khurtsia (1905-1949), and dates from a time when the centuries-old "neighborly" relations between the Abchasians and Megrelians was valued differently than it is today.

|

5. Mravalzhamieri, K'akheti, table song

|

Mravalzhamieri means "long-life-time". (Version from Guria: see vol.II:3; from Ratch'a: vol.II:6). Many table songs are nothing more than musical toasts, blessing the ones with whom one celebrates festivities, that they be strengthened to "withstand enemies" and to face successfully the inexorableness of the world: "Such is this transitory world: / Day wont to replace Night. / What animosity destroys, / love builds up again." Singing together creates a mode of communication which good wine and nice words cannot. The Mravalzhamieri from K'akheti is an example of how an individual can be enthusiastically swept up out-of himself by joint music-making. The bass line, sung collectively, drives the music upward 5 diatonic steps, only to let it suddenly drop 4; the next verse so must begin a tone higher. The diskant singers (D. Shanidze, M. Tch'itch'nadze) can choose to end the song here, or risk another verse. The interaction among the singers is also to be remarked in details of the musical setting. Refusal to integrate a modulation by non-accommodation of the required musical material, or its provocation by anticipation of new material, allows a living musical organism to develop, each voice able to influence the others by its behavior.

|

In the Middle Ages an influential power in the Near East, the unified Georgian kingdom disintegrated into small kingdoms and principalities after Mongol raids devastated it and the fall of Constantinople cut it off from western Christianity. Only by fighting continual defensive wars and by paying heavy tributaries, could the small kingdoms and principalities between the Osmanian and Persian empires preserve a semblance of independence. With time, the greater powers also succeeded in playing the Caucasian peoples one against the other. Readiness to do battle was for centuries in Caucasus essential for survival. The many songs of horsemen and warriors to be found all over Georgia give evidence of this:

|

6. Mkhedruli, Imereti, horsemens' song

|

"To go to war are those happy, / who own a good horse, / to return and enter one's home, / he, who has a good wife. / Better than a disgraceful life, / is an honorable death. / What animosity destroys, / love builds up again."A rare exception, the here especially important, collectively-sung bass line begins this song. The antiphonal form of the horsemens' song is highlighted by Ensemble Georgika's oppositional use of soloists (D. Shanidze, M. Tch'itch'inadze, Sh. Lortkipanidze) and choir.

|

| 7. Orira, Guria, warriors' song |

This warriors' song is also for 2 choirs. A heightening of intensity is achieved in the second part by shortening the sequences, this effect can also be heard in work songs (16) and circle dance songs (15). The words (oira divo dela, etc.) have no specific meaning. As often happens in Guria (16), the diskant is sung with a forced falsetto (D. Shanidze). Gamqivani (crowing like a cock) is the Gurian name for this technique. Georgika bases its interpretation on a 1907 recording by an ensemble from Mak'vaneti, which included members of the famous singer family, Erkomaishvili.

|

8. P'at'ara saqvarelo... Guria, table song

|

The love song is another example of Gurian polyphony for 3 soloists (see 1). D. Shanidze, Archil and Malkhaz Ushveridze utilize in this purely solistic version the ghighini (mezza voice) vocal technique, also found documented in older recordings by the singer, Vladimer Berdzenishvili. Typically Gurian is the text, where serious matters like love were often rogishly treated:

|

"My dearly beloved, / why did you kill my heart? / I brought you up in a cage / like a May nightingale. / I fed you with sugar, / also with cheese and with bread. / You, my executioner, my scorcher, / you, my next-door neighbor, / the fire that you aroused in me, / how will I appease it?"

|

9. Tsoli gamididgulda... Kartli

Solo: Sandro Mirianashvili

|

"My wife became incensed with me, / she turned away from me. / I promised her a silk garment, / she turned to me again. / But again she turned away, / this time I promised her a silk shawl, / she turned to me again."

|

10. Nana, Guria, cradle song

|

|

"This cradle is of mulberry wood; / in it a boy seemingly of crystal." |

Some of the lullabies for several voices of Georgian women, have long since lost their original function, becoming, as lyrical songs, popular in their own right. Singers who still command mastery of traditional improvisation have become rarities in Georgia today. With this goal in mind, Georgika has created its own variant and has added this to their series of recorded lullabies (vol. II, 8-10).

|

|

The following 2 songs take us into the secluded world of the high mountain-dwelling Svaneti. The leading middle voice moves here within a narrow intervallic range, which the two outer voices outline using repeatedly interrupted parallel movement. The music of the Svaneti accompanies equally rich, orally handed-down poetry of unrhymed verse.

|

| 11. Mirangula, Svaneti, epic |

Accompanied by the knee violin ch'uniri (M. K'asradze), whose 3 strings are bowed simultaneously, and the 6-, 7-, or 9-stringed harp changi (A. Khizanishvili), this song gives us an impression of the erstwhile clan-lifestyle of these mountaineers: unsuccessfully a mother tries to keep her only son from the rages of blood feuds and predatory raids, by raising him in a defense tower (murqvam) usually occupied only in times of emergency. That the laws of vendetta do not come to pass because he was able to kill his murderers himself, is small comfort.

"O you poor Mirangula, / your mother's only son. / Solicitously she held you in the tower, / where you were brought your meals. / Damned was that Wednesday evening, / when Mirangula was brought his dinner. / Mirangula was not at home, / having set out against his enemies. / Out the window saw the mother. / He stands on the mountain Matchkhpar. / O Mirangula, your mother's child, / you have done everything necessary and unnecessary, / this becomes your last journey."

|

12. Perkhuli, Svaneti, circle dance

|

| "Dali gave birth on a cliff, / gave birth on a white cliff, / gave birth during the day and into the night. / Below a wolf waits, / overhead ravens circle." |

Dali, a holy being of bewitching beauty in Svanetian mythology, is protectress of game in a wilderness untouched by man. She has an ambivalent relationship with hunters. If she takes one as her lover, she becomes severely jealous and forbids him any contact with mortal women. The newborn child falls from the cliff and is rescued from the claws of the wolf by a hunter. Of the 3 rewards which Dali offers him, he chooses the successful yearly shooting of 9 ibex. However, he doesn't fare well: one of the ibex has golden horns and of course, the hunter takes aim at him first. The bullet rebounds and strikes the hunter himself. He hadn't recognized the significance of the golden horns: they indicate that Dali has taken this animal form. According to some versions, this in Svaneti well-known text forms the beginning of the Amirani epic: the rescued child, who hardly born speaks with his mother, is no other than Amiran, the Georgian Prometheus. Georgika realizes the characteristic antiphony of the circle dance by alternating chorus and soloists (D. Shanidze, M. Tch'itch'inadze, Sh. Lortkipanidze).

|

13. Lomo shen lomis mok'lulo... Tusheti, lyrical song

|

All over Caucasus it is tradition for women to go to great lengths wailing for the dead. Especially in mountainous regions the improvised texts for these lamentations are stylistic masterpieces. They even influenced the lyric-heroic genre, to which this song belongs. "Lion, you by a lion slayed / on the edge of the meadow of Busni, / who colored the shoulder / of your shirt so red? / Who dared rule over you with a gun, / you the owner of many sheep? / Now, (arms like the) branches of the poplar tree / are laid upon your heart. / With my utmost I would weep for you, / if I did not respect my husband, / Lion, you by a lion slayed / on the edge of the meadow of Busni." M. Tch'itch'inadze is accompanied on a 3-stringed lute, the panduri, by Z. Sidamonidze.

|

| 14. Gandagan, Atch'ara, dance tune |

The chonguri, the counterpart to the East Georgian lute, panduri (see vol. II:7 and 16), is common to all of West Georgia except for the mountain regions Svaneti and Ratch'a. Like the latter, mainly used to accompany song, the chonguri is also occasionally employed for dance music, as in this solo piece from Atch'ara, a place in the extreme southwest of Georgia, long occupied by Turks. It offers A. Khizanishvili plenty of opportunity to demonstrate the possibilities of this rather delicate-sounding instrument: two-part writing with a wandering drone, melodies and virtuoso runs enveloped in 3- and 4-note chords. The chonguri has a fingerboard without fretts, and in addition to 3 long strings tuned to a major or minor triad, a considerably shorter fourth string (zili), whose pitch remains constant (a seventh or octave above the lowest string). Although this string is the highest in pitch, it is from the left, the third, so that a long string with variable pitch possibilities lies at the edge of the fingerboard.

|

15. Harira, Samegrelo, circle dance

|

Samegrelo's circle dance is more similar to Abchasia's than to Svaneti's. In Svaneti , all of the singers of the two strictly alternating choirs intone the text, whereas here it is only sung by the one in the center of the circle of dancers. Not only musically does he seize the initiative, often he will integrate elements of pantomime into his dance. In Harira, sung by Georgika in a version handed-down from Nok'o Khurtsia, this happens in the - also independently presentable - second part. Except for several rallying calls to the circle dancers to sing the bass line vigorously, D. Shanidze, the soloist, is completely free of textual obligations and thus enjoys great liberty improvising over the simple ostinato sung by the circling ring dancers.

|

| 16. Elesa, Guria, work song |

Like Orira (7), recorded by the vocal ensemble from Mak'vaneti in 1907, this antiphonal song also requires use of the vocal technique Gamqivani (D. Shanidze and L. Veshap'idze). In the version presented here, Elesa signals the end of a long work day in the corn fields. This is also occasionally connected with a pantonmime; the singers capture the owner of the field and tie him to a forked branch. "Why do you sow so much and torment us thus?", they ask and hold him until he promises gifts.

To hoe his corn field the owner had proclaimed Nadi. Perhaps his familiy did not have enough workers at their disposal, perhaps he preferred Nadi because it transforms the extremly tiresome work into a celebration. Who was able, hurried to help him (gratiously, of course). "One went to Nadi as gladly as to a wedding", because a whole program of songs tailored to the work (so-called Naduri, see vol.I:1; vol.II:14) made one easily forget back pains and exhaustion, and certainly the refreshments prepared by the also-toiling "host" left no desires unfulfilled. Along the Black Sea coast, Elesa is the name for songs which have many different purposes: Pontian Greeks and the Lazen (linguistically related to the Megrelians, today mostly living in Turkey) sing Helesa when pulling fishing nets and boats out of the sea, Gurians and Atch'arians when they haul tree trunks into the valley, Abchasians at table when several already declare that they are through drinking. Variants of this name (Leison da kiria in Samegrelo and Kilelesa in Abchasia) lead to the assumption that it derives of Greek words from the liturgy kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy upon us).

|

17. Orovela, Kartli, K'akheti, ploughman's song

|

In East Georgia the climate is dryer, the earth - although extremely fertile - harder than in West Georgia, where field work with the hoe generally offers an occasion to sing. Here one also works together, as not everyone owns his own plough and enough oxen. Sometimes as many as eight yoke of oxen and buffalo will be harnessed to a plough. The order in which the fields are ploughed is determined by the amount of work one renders to the collective. The poorest are themselves the oxen-drivers; they must also guard over the animals remaining in the field overnight. The interjections in the song are for them. The large number of persons taking part in the tilling make part-singing again possible; here is also the reason for the abundance of textual material, as compared to the relative uniformity of the music. The texts concern themselves with the workers, the ploughman (gutnis deda, "mother of the plough"), the oxen-drivers, often the oxen and buffalo. Our text directs itself to the plough, the "bread-winner", and its parts; "the small wheel, that sings an accompanying voice to the plough, the ploughshare, that should pull out the weeds by the roots". The meaning of the word orovela, which also occurs in Armenian plough songs, has not yet been settled. Orovela also designates the songs sung while threshing: work accomplished with a threshing-board, again pulled by oxen.

|

|

Georgia embraced Christinity in the 4th century. In spite of the increasing spread of Islam in the Near East - and in the 17th century also in North Caucasus - Georgians held staunchly to their faith. It remains today an important element in their national identity. The year is thus marked by the many holidays of the Georgian-orthodox church calendar. These celebrations have also, as elsewhere, been assimilated together with pre-Christian rituals and ideas, into non-ecclesiastical traditions. The main holidays, Easter and Christmas, are prepared for by extensive fasting, which in Georgia means renunciation of all foods of animals origin. So, it is no coincidence, that appreciation for the vocally-offered "best wishes" for both holidays is expressed with gifts of food.

|

18. Tch'ona, Kartli, Easter song

|

In most of the regions, traditional Easter songs make use of the orthodox felicitation, "Christ has risen". Alone in Kartli and Imereti, perhaps originating from pagan fertility cults, have forms been preserved which can also be found in the mardi gras plays, Berik'aoba or Qeenoba, that open the Great Fast. Distinctive of the East Georgian song tradition is the collectively sung two-tone drone accompaniment (see 5,17); a seldom occurrance however, are the rising melodics of the opening of this song, sung by the lead singer. D. Shanidze and M. Tch'itch'inadze present a well-known version, already recorded in the 1930's by Vano Mtch'edlishvili (1903-1970). "Mother, I will sing Tch'ona to you, / if you are not in mourning. / God on High, may He bless for you / the one lying there in the cradle. / Alatasa balatasa / I will hang a small basket. / Mother, give us an egg, / God will repay you profusely."

|

| 19. Alilo, Ratch'a, carol |

Almost every region in Georgia has one or more special Alilo's (Halleluja's), with which a group of at least 3 young people go from house to house on Christmas Eve, wishing the residents Merry Christmas and - in our version - many New Years. Although the text emphasizes that they are Christ's messengers and not beggars, one of them carries a basket for presents (meat for shish-kebabs, bean dishes, bread, often also money). Georgika sings a version after the local ensemble Sagalobeli of Ambrolauri, recorded 1994 by Th. Häusermann and Evt'ikh Gabunia. Characteristic for the style of this region, where elements of east and west Georgian tradition are united, are the upward aspiring modulations and the intermittent parallel motion of all three voices. Only in the mountain region Ratch'a are the Alilo begun one after another by both diskant soloists (D. Shanidze and M. Tch'ich'inadze).

|

Georgia is literally overrun with churches.The liturgical hymns, which once filled them, are presently beginning to be revived again. From the 8th to the 11th century, various schools of hymnography translated the orthodox liturgy from the Syrian and Greek into Georgian and created within the orthodoxy perhaps an unrivalled tradition of part-singing which, in most cases orally handed-down, lived on into the 19th century. The 9 canonic sdzlispiri (Greek: Heirmos), on scriptural texts, and the ochita (Greek: Troparion), calling on the saints to intercede, are based on a unified system of 8 melody-complexes, similar to the Byzantine Oktoecho and the Roman Church's modes. Their structural organization for part-singing varies considerably, depending on local tradition. An intense collectors' activity ensued when the church service became Russianized, due to the abolition of religious independence for the Georgian-orthodox church. From this activity the sdzlisp'iri (21) from the evening liturgy (mtsukhri) has come down to us, published according to familiy tradition in 1897 by the priest V. K'arbelashvili of K'akheti. Although most of the churches were closed down, and religious practice repressed after the annexation of Georgia in 1921 by the Soviet Union, a variety of hymns, distinguished by very individualistic harmonies, were preserved, mostly in West Georgia. The two hymns from Guria (20, 22), corresponding to the preceding traditional songs (18,19), are taken from Christmas and Easter church services.

|

| 20. Tropar of New Year, Gurian tradition, first mode |

According to the orthodox church calendar, the 1st of January is dedicated to the church father, Basilios the Great, of Kappadozia (329-378). "Your reputation has spread to all corners of the world where your word has been heard, with which you, in a manner pleasing to God, have preached the faith, revealed the essence of all things mortal, illuminated the ethics of Mankind and graced this priesthood of God. Holy Archpriest Basili, beseech our Lord Christ that he have mercy upon our souls."

|

21. Movedit taqvanis vstset... Eastern Georgian tradition of the Karbelashvili priest-familiy, eighth mode

|

"Come let us pray to God, our Father / and prostrate ourselves before Christ, our Lord."

|

22. Aghdogmasa shensa... Easter tropar, Gurian tradition, sixth mode

|

Davit Shanidze, Mamuk'a Tch'itch'inadze, Shalva Lortkipanidze, soli."The Angels in Heaven extol your Resurrection, Christ our Savior. Make us here on earth pure of heart and worthy to sing your paises."

|

Thomas Häusermann - English translation: Margaret Shu-Ching Wu

|