|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

|

1. Tös tartkhany – tös tartkhany (spirit-calling), Saghai people - 1:60

2. Toghys khulas sunu küreng attygh Siber Chyltys – alyptygh nymakh (heroic epic), Saghai people - 21:50

3. Postai Aryghdyng syydy – kip-chookh syydy (dirge song from a story), Khyzyl people - 4:37

4. Akh tan – instrumental, Saghai people - 3:49

5. Kharakh chazy – saryn (lyric song), Saghai people - 3:22

6. Alajaam – yr (lyric song), Khyzyl people - 5:03

7. Taias yry – ibîrîg syydy (dirge song), Piltîr people - 3:07

8. Tagh taiyghdyng alghazy – tagh taiyghdyng alghazy (worship song), Saghai people - 10:42

9. Pai Pituncha – yr (lyric song), Khaas people - 2:18

10. Apsakhtar yry – yr (lyric song), Khaas people - 4:28

11. Kishteiler yry – yr (lyric song), Khaas people - 2:04

12. Kök tigîrdegî chyltystary – yr (lyric song), Khyzyl people - 0:58

13. Khangyra khangyr – yr (dirge song), Khyzyl people - 4:54

14. Khazyr chyllar – yr (lyric song), Khyzyl people - 3:05

Ensemble

The ensemble Ülger from Abakan in the Republic of Khakassia was founded in 1989. They have committed themselves to revive and keep alive their tradition in music as well as dance. Ülger means “Pleiades”, the winter stars that rise in early autumn and announce the long, dark, cold season. Legend has it that Ülger rides through the sky on a two-headed horse, scattering extreme cold and snowfall on earth. People believed the Pleiades to be the place of residence of powerful heavenly beings who decided upon a human being’s fate.

The Pleiades: The Mushins plays an important role in the Buryat-Mongolian cosmology. Already in earliest times, people believed that the Tenger (powerful heavenly creatures) of the western direction meet at the Pleiades in order to discuss how to help mankind in fighting death and diseases. In this gathering, they created the Eagle, the first shaman. The Pleiades - Mushins also plays an important role in the epic Geser and the creator Ülgen of the Altai population.

The Khakas people have been known for their rich storytelling traditions, both in epics with throat singing as well as prose, just like their neighbouring Turkic tribes. Songs and stories are often performed in accompaniment of the lute or the box zither. Besides storytelling, they had a wide range of songs for ceremonies, rituals, which lead the people through their life from birth to death, as well as songs for the various seasons. The Khakas also have a limited repertory of pure instrumental pieces and various ceremonial dances. In the evenings or during the long winter nights men as well as women used to gather and entertain therewith. They have attempted to copy the sounds of nature as well as those created when people are working. Hunters and breeders used animal sounds to call or attract their flocks. The oral transmission of their traditions was lost due to forced Russification and the modernization of folklore. Seasonal rituals, clan meetings and shaman sessions were prohibited or firmly discouraged, such as ritual performances at holy sites. Life cycle events like weddings, birth or death, ceremonies for infants and small children, death watches or prayers before the hunt have been lost. When Soviet politics loosened in the mid-1980s, most traditional practices had become rare or had disappeared altogether, especially ritual ceremonies, and epic performances of tribal history having historic importance have become neglected. The non-ceremonial music had turned into folkloristic stage music.

Now young musicians seek to revive these traditions. They move away from the Soviet-based reconstructed “folk music” in search for the authentic patterns of their ancestors. They have started to collect repertoire from the few remaining traditional performers in the villages still alive and from archived audio recordings and music manuscripts. They try to revive the past when village elders are visiting, and they further search the scarce historical ethnographic sources of their ancestors. The ensemble wants their repertory to play an important role in the process of revival.

In their repertoire today there are included heroic epics with throat singing and accompanied by the wooden box zither or lute, as well as old songs describing everyday life: at work, at the occasion of weddings, laments, ceremonial and prayer songs addressed at the heavenly owners of the sky, the mountains, the water, fire and other elements. Many songs were handed down with little or no text at all, which is why the ensemble rescues these old melodies from oblivion by creating instrumentals with them, or finding fitting traditional poetry to them. The aim is to conserve cultural traditions and values for a young generation, using the mother tongue.

Since 2003 the ensemble has been performing under the artistic guidance and direction of Aycharkh Sayn – a gifted musician, virtuoso throat singer, multi-instrumentalist and storyteller. The ensemble has participated in festivals and competitions in Russia and abroad. They have performed in Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Switzerland, France, and the United Kingdom. In 2005 Ensemble Ülger performed at the Sayan Ring Festival of Ethnic Music in Siberia, and since 2006 they have been touring the south of France several times, the last time being in 2011, when they performed at the Russian Art Festival in Cannes. In February 2012 they featured at the Russian Maslenitsa Festival in London.

Khakassia and the Khakas people

The Khakas people are a Turkic-speaking minority, who settled in a region of endless steppes and mountain taiga at the upper Yenisei and in the Minusink Basin, at the foot of the Sayan-Altai mountain range in southern Siberia. Their Turkic-speaking neighbours are the Tuvans, Altaians and Shor people.

In the 17th century A.D. a part of the tribes migrated to the Tien Shan, thereby forming today’s Kyrgyzstan. The migrated Kirghiz have left behind a rich culture as well as an old runic writing.

In the Orkhon Inscriptions dating from the 8th century A.D., there are described the bloody wars and fights taking place in the 6th century against the tribes of the Göktürks, Xueyantuo and the Uighurs in the Han period. There are still songs from the time of this war for autonomy reminding and remembering these conflicts. Petroglyphs, tombs, ritual sites and deer stones tell of days and tribes long gone, which have all settled there from the 3rd century B.C. on, as has been proven by archaeological findings.

Those who remained settled where they live today, in the plains and steppes west of the river Yenisei, upstream in the mountain taiga and in the valley of the Abakan and its tributaries. In 1707, after strong resistance, the land was annexed by the Russian Empire. Songs recalling episodes from this struggle for autonomy have been sung to this very day. In 1923 the country came under Soviet rule, until in 1992 it got the status of an autonomous republic within the Russian Federation.

In today’s Khakassia, various ethnical groups settled between the 6th and the 13th century.

The Khakas tribes themselves were conglomerate of such mixed ethnic groups. In this area, there also settled Kets (the Khanty people) and the Nenets people (Samoyeds) belonging to the tribes of the Uralic group and speaking a Finno-Ugrian language. They formed tribal communities and for a long time were vassals of various Turkic speaking confederations (Dzungars, Oirat Alliance), among those also the Khirgiz and a Manchu-Chinese Qing Dynasty. In the early Soviet period they were restructured as “Khakas”, but they call themselves “Tadar”, with people mainly adhering to their lineage (family name) and clan (söök). In the North of today’s Khakassia there live the Khyzyl people, in the central part the Khaas people. The steppe Khakas (Khaas and Khyzyl) traditionally were pastoralists who moved from winter to summer pastures and supplemented their diet with hunting and agriculture. In the south, there were the Taiga tribes, the Saghai, Khoibal, and Piltîr people, who were fishermen, hunters and gatherers, living on agriculture.

Women held an important place in the Khakas society, which is reflected in many poems and stories of heroes (epics).

Female warriors have been great heroes against external enemies. Women wear a "pogho" (see right), a female breast ornament made of cowry shells, with pearl buttons and colourful beads sewn to the leather or textile.

The poghos build a bridge between generations and act at the same time as a spiritual protective shield that protects female fertility and thus secures offspring.

|

|

Worldview, ceremonies and rituals

The Khakas universe consists of three worlds: the upper world with Khudai or Khan Tigîr (“Ruler Sky“) and other spirits having supernatural powers; the underworld with Erlik, the ruler over the evil powers, and the middle world in which we live together with a wide range of spirits, of which the mountains spirits have the greatest impact on human life. People believed to be under the rule of supernatural powers, which they had to subordinate to and which they had to offer sacrifices to. This constitutes an animist worldview (animism – magical belief, religion - all human beings, animals and elements in nature have a soul – a ghost having differing meanings and differing characters). In the elements (fire, water, wind), the spirits have found their homes, furthermore in rocks, trees, mountains and at very particular sites. The belief in nature and to be in compliance therewith, these are two very important matters, which is also visible in texts. Animals live in societies parallel to the human one. Animals and human beings can enter each other’s world and even - temporarily or permanently - change shape.

After death people leave for the “other world“, returning to their relatives who reside in either the ancestral mountain or somewhere in the North. Spirits, who have not succeeded in setting over, will return as evil spirits.

The year is marked by spring, summer, and autumn ceremonies and rituals. The year (chyl pazy) begins in March, with the spring equinox, this constituting the beginning of spring. During the chyl pazy ceremonies the dark, cold season is bid farewell and the warm season met with prayers and coloured ribbons (chalama) that are tied to the sacred birch (pai khazyng) in prayers for a fruitful year. In June, the celebration of the first mare’s milk (tun pairam) is celebrated with riding, wrestling, archery and singing contests. In autumn nature is given thanks for a prosperous spring. Formerly also the return of migrating birds was celebrated in spring. As is known from text findings, migrating birds seemed to have been an important topic for nomads in Siberia and Central Asia. In multi-annual cycles, there were performed extraordinary sacrifice rituals for the spirits of the sky, the mountain or the water.

The spirit owner of nature (eeler) and in particular the spirit owner of the mountains (tagh eezî) are frequently addressed, in personal everyday prayers to show respect and maintain good relationships, and in community invocations and prayers to request the well-being of humans and animals. For misfortune, illness, and catastrophes a range of ritual specialists are invited who mediate between mankind and spirit world. They have helping spirits (töster), mostly in animal shape, whom they ask for help in order to influence the spirit world. Important ritual specialists are the shaman (kham), healer (imchî), and ritual cleaner (alaschy).

Ceremonial and ritual poetry is sung or recited with intoned speech or with overtone singing. Thanks, well-wishing and wish-praying poetry is used for many occasions in order to communicate in sessions and by way of praising words with the helping spirits. Therein these were asked to appear and help in order to manipulate the powers. The Khakas people do not know any praise songs (maktal) such as other Turkic tribes or the Mongols, through which the people may praise other persons, their home country, mountains, and so on using well-wished texts.

Alghys is performed to protect newborn children, a newly-wed couple, the family, community, and animals. Local spirits were also called for help, for protection, for a successful harvest, when entering new land or before hunting. Today, these are also sung as lyric songs. Invocations to the main spirit owners of nature were used to invoke and pray to the spirit owners of sky, mountains, water and taiga. Shamans and healers attempt to get the attention of their helping spirits with invocations and prayers and ask them to help in a session. In order to attract spirits, the people used whispered words and prayers, but also in addition whistling, shouting, moaning, exclaiming, animal imitations, reciting texts or singing songs and, in addition, frequently in accompaniment of a frame drum.

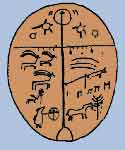

Drawings of prehistoric rock carvings by Aycharkh Sayn

Songs

| 1. Tös tartkhany – Calling to the help spirits |

| Spirit-calling (tös tartkhany), Saghai people, as Aycharkh Sayn heard it from Sampir Kuchenov, Sapron aaly (Safronov), Askhys aimaghy, Abakan. |

| - Aycharkh Sayn: khai in küülîp style |

| With tös tartkhany shamans and healers summon their helping spirits (töster). When the spirits have arrived, the performer continues with special alghys to guide the spirits in solving the problem. |

| In his childhood Aycharkh Sayn regularly heard his granduncle Sampir Kuchenov perform such ritual poetry. Sampir Kuchenov was a healer. With these words he called his helping spirits, who then assisted him in curing people. |

|

| 2. Toghys khulas sunu küreng attygh Siber Chyltys – – Siber Chyltys on his nine-fathom-high brown horse (1) |

| Fragments of a heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh) from Aycharkh Sayn, clan Choon Sayn, Saghai people, Sapron aaly (Safronov), Askhys aimaghy, Abakan |

| - Aycharkh Sayn: khai in küülîp style, narration, chatkhan |

|

- “Akh chaiaan Ailan sykhkhandagh / ai purghunu chirge tüskendeg. / Ardaspas khudainyng sözîneng / aspakh synnar tay altyna chech parghan ...”

|

|

- “When the universe started moving / dust fell down from the moon. / With the words of the highest creator / icy white peaks were flung in the air... |

|

| Here he performs two fragments from his epic about hero Siber Chyltys (Skilful Star) in attygh nymakh style (“story on horse”), that is, with khai in küülîp style accompanied by chatkhan, in alternation with unaccompanied intoned speech, and interspersed with instrumental interludes. |

| Aycharkh Sayn first describes the creation of the world, with the appearance of land and mountains, water with its fish, trees and the taiga with birds and wild animals, and the steppe with its people, settlements, and livestock. He then recounts Siber Chyltys’ first fight, his battle with Khara Molat (Black Steel), an evil warrior who intends to fight down all hero warriors. All heroes fight with supernatural powers and the help of favourable spirits, freeing the people from suppression and plight. After being victorious over Khara Molat, Siber Chyltys returns home, flops down in a seat, and takes a well-deserved rest. |

Aycharkh Sayn takes an exceptional position among contemporary performers. In the early 1990s he was driven into storytelling by an ancestral spirit from his mother’s lineage. He is therefore able to perform authentic alyptygh nymakh for hours.

|

- (1) A fathom is an ancient measure of length based on the distance between a man's outstretched arms (1.5 to 1.7 m). Siber Chyltys’ horse consequently is about 14-15 metres high.

|

|

|

|

Aycharkh Syn - tüür

|

Altyn Tan Tayas - topchyl-khomys

|

|

| 3. Postai Aryghdyng syydy – Postai Arygh’s grief |

| Dirge song from a kip-chookh story (kip-chookh syydy), Khyzyl people, Khyzyllar aimaghy, transmitted orally. |

- Altyn Tan Tayas: voice

- Aycharkh Sayn: chatkhan

|

| This is one of the oldest Khakas songs documented together with the melody. It is a dirge song from a historical kip-chookh story about Öjeng Pig, the last leader of the Khakas people. His death even affected people who were not bound to the ruler. |

Dirge songs differ from dirges as they mourn for a deceased person beyond the funerary context and are styled like a song. In this dirge song, the hero’s wife, Postai Arygh, bewails her killed husband. Her grief, however, exceeds the private sphere, as the tragic death of this Khakas national hero is closely connected with the historical fate of the Khakas people: after Öjeng Pig was killed, the land was incorporated in Russia and the people finally subjected to foreign rule.

|

| Due to the legendary dimension Öjeng Pig got in the people’s memory, the song has been handed down over the centuries and today exists in many versions. Altyn Tan Tayas and Aycharkh Sayn perform a version from the musical Kurbizhekov lineage. |

|

| 4. Akh tan – Gentle spring breeze |

| Instrumental piece with improvised melodies (kögler), Saghai people, Askhys aimaghy. Following the manuscript of a recording by Aleksandr Kenel in 1940 at the archive of the Khakas Research Institute XAKNIIYALI, Abakan. |

| - Albychak Sayn, yykh |

| In the 1940s Aleksandr Kenel noted down countless song melodies without text (kögler). By improvising on some of these traditional melodies collected by Kenel with his yykh, Albychak Sayn brings them back to life. Here he evokes the refreshing spring breeze one enjoys on a hot day. |

|

| 5. Kharakh chazy – Tears |

| Lyric song (saryn), Saghai people, as sung by Yakov Kuchugeshev from Pydyrakh aaly (Butrakhty), Tashtyp aimaghy. Recorded by Aleksandr Kenel in the 1940s, published in his song collection “Khakas chonynyng köglerî” (Abakan, 1955). |

- Tülber Pögechi: voice

- Aycharkh Sayn: khazykhtar |

| This song documents the difficult living conditions many Khakas people faced in the old days. A wage worker, forced to emigrate in search of work, deplores his separation from home, family and homeland. As he makes his way through the taiga, he calls to mind his homeland and weeps. |

|

| 6. Alajaam – My two-coloured horse |

Lyric song (yr), Khyzyl people, as sung by Aleksandra Charochkina from Kostino, Sharypovskogo rayon, Krasnojarski kray. Recorded in Abakan by Aleksandr Kenel in 1944, published in his song collection “Khakas chonynyng köglerî” (Abakan, 1955).

|

- Altyn Tan Tayas: khobyrakh

- Tülber Pögechi: voice, aghas-khomys

- Albychak Sayn: yykh

- Aycharkh Sayn: chatkhan

- Lunic Ivanday: syylas, khai in kharygha style

- Mirgen Irgit: khongyros, sang

|

| Horses are highly valued by the Khakas people. The singer here praises her fast riding horse. |

| - “My two-coloured riding horse / resembles a girl with many small plaits. / When I ride it saddled-up / it resembles a swift bird.” |

| The song’s melody moves in big leaps and with pronounced rhythms, typical for the Khyzyl people. |

|

| 7. Taias yry – Taias’ dirge |

| Dirge (ibîrîg syydy), Piltîr people, Pii aimaghy. From a recording from a private collection. |

| - Altyn Tan Tayas: voice |

| This is the dirge of a woman called Taias, who mourns for her husband. In this dirge Taias recalls how she got acquainted with her husband in her youth, and how they lived together in harmony. |

It is an ibîrîg syydy, a ritual performed at the multiple wakes during the first year after death to see off the deceased’s souls one by one. The text is close to a funeral dirge (söök syydy), when the bereft person mourns over the corpse, bewailing the beloved with words like “Now you are laying here. Why did you abandon me?”

Unlike the funeral dirge, which includes cries, sobbing and slidings of the voice, the post-funeral ibîrîg syydy is performed as a song. |

|

| 8. Tagh taiyghdyng alghazy – Worship for a mountain spirit owner |

| Worship for a mountain spirit owner (tagh taiyghdyng alghazy), Saghai people, as performed at Chazui near Sapron aaly (Safronov), Askhys aimaghy. Documented by Nikolai Katanov in 1892, published in Part 9 of Wilhelm Radlov’s series “Obraztsy narodnoi literatury tiurkskikh plemen” (Sankt Peterburg, 1907). |

| - Aycharkh Sayn: khai in küülîp and kharygha styles, tüür, khazykhtar, sangyros |

This is an alghas (invocation) that was performed for the spirit owner of the mountains (tagh eezî) at a tagh taiygh (mountain worship ritual) of the Sayn söök (clan) to which Aycharkh Sayn belongs.

This sacrificial mountain ritual took place every three years in July and was led by a shaman belonging to the söök, but from the neighbouring region of Chis chirî (Shoria). The ritual was to be attended only by male clan members; women meanwhile gathered at the foot of the hill. The prayer was performed by a shaman as it was an appeal to the highest power man can address. The shaman asked the tagh eezî for beneficial weather conditions, prosperity for people and livestock, and protection for the children and from diseases. |

|

| 9. Pai Pituncha – Rich Pituncha |

| Lyric song (yr), Khaas people, as sung by Pelaga Ayoshina, Chookhchyl aal (Troshkino), Shira aimaghy. Recorded by Aleksandr Kenel in 1945, published in his song collection “Khakas chonynyng köglerî” (Abakan, 1955). |

| - Tülber Pögechi: voice |

| Many versions exist of this popular song that has extensively been handed down from generation to generation. Tülber Pögechi’s version narrates of a man called Fedot, who cheated on his beautiful young wife and kept her prisoner for two months, until she murdered him with an axe. From Khyzyl Char (Krasnojarsk, at that time the closest town) an inquisitor was sent to investigate the murder. The man took the young woman to Khyzyl Char in order to lock her away, but on the way back he fell in love with her because of her extraordinary beauty. He prevented her from being imprisoned and married her. The first child she bore him, however, was Fedot’s. |

| The song has a long melody, typical for the Khyzyl people. |

|

| 10. Apsakhtar yry – Song about the elders |

| Lyric song (yr), Khaas people, as sung by Yevdokia Abdorina from Khyzyl aal (Kobezhikov), Shira aimaghy. Recorded by Aleksandr Kenel in 1945, published in his song collection “Khakas chonynyng köglerî” (Abakan, 1955). |

| - Albychak Sayn: voice (khai in kharygha style), yykh |

| A song by a talented singer from a musically gifted lineage. That reflects on some core values of the Khakas people: respect for the elders, keeping to traditions, and artistic modesty. |

| - “The roads with many side-roads / were built by the elders. / The songs I sing for you now / I heard from the old people.” |

| – (See also song no. 12 Kök tigîrdegî chyltystary, no. 14 Khazyr chyllar, and Vol. I: song no 1 Pig tug) |

|

| 11. Kishteiler yry – Song from the Kishteev lineage |

| Lyric song (yr), Khaas people, as sung by Mirgen Irgit’s great-grandmother Anna Sarlina from Arshan aal (Arshanov), Altai aimaghy. From a recording 1986 at the archive of the Khakas Radio, Abakan. |

| - Mirgen Irgit: voice |

| - “I am a daughter of my father. / I belong to the Kishtei lineage.” |

| Mirgen’s great-grandmother sang this song at an aitys (singing contest) in 1986. She revealed her identity by pointing to her ancestry. |

| Following Khakas tradition, people create songs on a fairly limited number of melodies that differ from area to area, and in turn vary slightly from village to village, and sometimes from lineage to lineage. This song, however, has a melody not encountered anywhere else, not even among the relatives; Anna Sarlina created it herself. |

| – (Anna Sarlina – see photos in Traditional songs of the Khakas people Vol. I and Vol. II) |

|

|

|

|

Mirgen Irgit, voice

|

Tülber Pögechi, aghas-khomys

|

Anna Sarlina on a wedding

in Arshan aal

|

|

| 12. Kök tigîrdegî chyltystary – The stars from the blue sky |

| Lyric song (yr), Khyzyl people, Khyzyllar aimaghy, as sung by Oktiabrina Abdorina. From a recording in 1970 at the archive of the Khakas Radio, Abakan. |

| - Altyn Tan Tayas: voice |

| In this song Oktiabrina reflects on the strength of her people, who can overcome hard times. |

| - “The stars of the blue sky / reflect in the eyes like silk. / When I look at my hard-working people / they seem like heroes to me. |

| The melody moves in big leaps, characteristic for the Khyzyl people. |

|

| 13. Khangyra khangyr – Gaggling geese in flight |

| Dirge song (yr), Khyzyl people, as sung by Anna Kurbizhekova from Naa aal (Ustinkino), Khyzyllar aimaghy. From a recording by Albina Kurbizhekova, private collection. |

- Altyn Tan Tayas: voice, khobyrakh

- Tülber Pögechi: aghas-khomys

- Albychak Sayn: yykh

- Aycharkh Sayn: voice, chatkhan

- Lunic Ivanday: syylas

|

| - “Khangyra khangyr khastar khustary, tidîr / Khongyrazyp kilîp irtîsklepcheler, tidîr...” |

| The text is built on kha-, kho-, and khu- alliteration, elaborating on the onomatopoeic verbs for the gaggling, ringing sound of geese (khang-, khong-, khung-). |

| - “A flight of gaggling geese flew slowly over. / Approaching with ringing sound, they passed by. / Like the geese I was singing when I came. / Why didn’t you stay with me, kharachkhayaghym (my little swallow)? / Under the light we lived together. / In the dark world we’ll live together again. / Under the sun we built ourselves a home. / In the invisible world we’ll settle down together again." (1) |

- (1) “Under the light, the sun”: among the living. “In the dark world, invisible world”: in the world of the dead.

|

| Anna Kurbizhekova elaborated on the funeral dirge of a woman who prematurely lost her husband and finds comfort in the hope to meet again in a next life. The mourner compares their living-together to migrating geese. Altyn Tan Tayas explains: “She sings about her husband who has gone to another world without her. May be in the next world they will meet again and continue to fly along like geese”. Needless to say that in a climate with such long, cold periods, migrating birds hold an important position – (see also Vol. II, song no. 21 Aghyn khustar). |

| Dirge songs vary from dirges as they mourn for a deceased person beyond the funerary context, are styled like a song, and often are called yr (song). This dirge song is an artistically elaborated funeral dirge (söök syydy – mourning over the corpse), in which the bereaved speaks directly to the deceased – (see also song no. 7 Taias dirge). |

| Anna Kurbizhekova (1913-1990) was a sister of khaijy storyteller Pödör Kurbizhekov – (see Vol I. song no. 4 Körbe ool takhpaghy), and herself a gifted singer, nymakhchy (storyteller without khai) and chatkhan player. |

|

14. Khazyr chyllar – Harsh years

|

| Lyric song (yr), Khyzyl people, Khyzyllar aimaghy, as sung by Oktiabrina Abdorina. From a recording in 1970 at the archive of the Khakas Radio, Abakan. |

- Altyn Tan Tayas: voice, topchyl-khomys

- Tülber Pögechi: aghas-khomys

- Albychak Sayn: yykh

- Aycharkh Sayn: khai in kharygha style, yykh

- Lunic Ivanday: tüür

- Mirgen Irgit: khongyros

|

| Oktiabrina Abdorina performed this song of her mother Sofia at an aitys (singing contest) in the 1970s, replacing her mother who renounced due to illness. It is a lyric song about respect for the elder generation and inter-generational understanding, and at the same time a sung alghys (well-wishing poetry) in gratitude to those elders. |

| - “You went through difficult years (the 1930s-1960s Soviet era), our elders / May your life be happy now. / Watch your offspring with satisfaction / and enjoy their peaceful life.” |

| The song has a long lyrical and melodies with big leaps and complex rhythms, typical for the Khyzyl people. |

|

|

|

Tülber Pögechi, Altyn Tan Tayas, Albychak Sayn and Aychark Sayn

|

Albychak Sayn, Tülber Pögechi, Lunic Ivanday and Mirgen Irgit

|

|

Performing arts

The Khakas people have a rich tradition in storytelling, performing epics in poetry and in prose, proverbs, sayings, wise phrases and riddles, fixed and improvised songs, dirges and laments, wedding songs, lullabies, working songs and game songs.

Text always prevails over music. These linguistic tools are means to tell or sing stories in a convincing and persuasive way. Poetry does have the power to enchant the audience, and for this reason it is performed according to fixed rules. Contextually, poetry is formed on observations regarding parallelism between human experience and natural surroundings.

The Mongols also know songs that are existent in verse form, without any refrain proper, with full vocal power and in the highest register. The melody is surrounded by a “coat“; there is sung a range of more than three octaves; the Khakas songs, however, are rather limited, covering frequently only one octave, with that of the Saghais restricted frequently to only one fifth. These songs are always subject to rather strict rules of presentation and performance. The form is quatrains, and the beginning of every single line is determined by the same vowel of the first word. Texts are adopted by other singers, and there are added some new improvisations: in this way, long stories (songs) are generated and created. The Mongolian people definitely sing these long songs when they are out alone in the steppe and only riding rather slowly. The repertory is a symbol of the freedom and the vastness of the Mongolian steppes and also accompanies cyclic rites of the year and ceremonies of everyday life. Long songs are also an integral part of festivities taking place in the round tents. Among the Khakas, however, such songs are not very common, it is further prohibited to sing in the open steppes or in the taiga, as this might attract the evil spirits. The Khakas also do not distinguish between long and short songs. For rites, there are used alghys (prayers, blessings, thanks), and in gatherings and meetings there are performed alghys and takhpakh (improvised songs).

In the Khakas society creativity has a supernatural source; it is conveyed in the dreams of the people. Such gifts and talents are not only handed down in a line (family), but they may also be awarded to individual persons. Due to the gifts provided by the owner spirits, man and woman are gifted. Skilled story tellers of epics (nymakh), as well as singers singing improvised songs, are supported in their performances by the owner spirits.

Every man and woman can be awarded the gift of creativity by a spirit. Skilled and gifted storytellers of epics and singers of improvised song (takhpakh) are supported during their performances by the spirit owners of nymakh, khai, or takhpakh. They receive instructions and inspiration in their dreams, and are inspired and supported while performing.

Songs were performed at all events where people met spontaneously or on organization, but especially at festive family gatherings and singing contests. People were allowed to sing at day and night, but only in and around the house and the village. For this reason, the Khakas, as opposed to the Tuvin, Altaian and Mongolian people, did not sing songs when travelling or riding the horse across the steppes. Singing in steppe, taiga and mountains is prohibited because it attracts evil spirits. The Khakas people therefore, unlike the Tuvans and Mongolians, do not have travel songs. Most songs can be performed by men and women alike, except for the songs that belong to gender-specific activities, such as (lullabies) cradle songs and work songs. In general, however, songs without throat singing are mainly performed by women, whereas epic storytelling using throat singing is more or less limited to men.

Some songs are integral part of specific occasions like family festivities and year-cycle ceremonies. Blessings (alghys) were recited or sung for welcoming and leave-taking. Love songs, courting songs as well as confirmation of marriage and dowry negotiations formed a rather impressive repertoire. In the context of death, various kinds of dirge (syyt) are sung. In the first year after death ritual dirges are performed: söök syydy (“lament over the corpse”) before and during the funeral and ibîrîg syydy (“lament at a post-funeral wake”) at the wake, to see off the souls of the deceased and thus ease the passage of the deceased into the other world. Later, people sing non-ritual dirges at home in order to commemorate the beloved.

The Khakas people have also songs that are not bound to specific occasions: takhpakh, a song with an improvised text, and saryn or yr, a song with set text and melody. With these songs, performed solo, performers can freely express themselves, sometimes to the accompaniment of a string instrument. Takhpakh are spontaneously improvised texts and give a description of the surrounding nature, one’s home country, a gathering or meeting, or another singer. Takhpakh singers show their talent in special singing contests called aitys. In such competitions two singers alternately compete with constantly improvised verses on a limited number of melodies, and try to outdo each other in originality and wit. Such singers are supported by their spirit owner, who gives them the ability to perform such inspired texts. Set songs are called yr (Khaas, Khyzyl and Khoibal) or saryn (Saghai and Piltîr), having more verses, an elaborated theme, and often more distinguished melodies. The majority of these songs are lyric songs, into which the performer integrates own thoughts and feelings about life and past events; some are work, game, or dirge songs.

The repertoire comprises a small group of dirge songs or laments (syyt) that are designated as lyric songs; dirge songs are ritual songs; laments having improvised texts are performed by a singer and tell of the person deceased and those he has left behind. Personal laments may be taken over by other singers, thus being slowly integrated into the common song repertoire.

Other dirge songs stem from epics or stories (kip-chookh) and constitute the oldest surviving form of the Khakas folklore. Laments are complaints about one’s misfortune, misery or suppression and are also often called “yr” ("song"). These laments are often sung by animals or human beings who have turned into animals and who sing about their harsh living conditions or unfair treatment - another display of the parallels to suppression and the life as vassals shared by the people.

The most prominent Khakas storytelling tradition is epic stories (“epic with a hero”) performed by specialized storytellers at meetings and gatherings during long winter nights – also to accompany souls into other worlds, or before hunting to please the spirit owner of the animal to be given the permission to shoot deer. Performance with throat singing and the box zither or lute was reserved for male performers and called “epic with a horse”. Unaccompanied recitals, being performed with intoned speech voice, are called “epic on foot” and may also be performed by women. An “epic on horse” sets off with an instrumental prelude. Then the storyteller tells the story alternating with throat singing and with repeated text having temporary shifts to a higher or lower tone and with unaccompanied intoned speech. The overtones of the throat singing create an extraordinary timbre texture that brings about the supernatural time-space feeling, in which the epic world comes to life. Every now and then the story is suspended with an instrumental interlude, a blessing, well-wishing expressions, songs or laments.

The most talented storytellers are provided with inspiration by their spirit owners and they are called eelîg khaijy (kaichi). They could endlessly sustain their performance. Such a story could last for several nights in a row, being interrupted only by short breaks. The storytelling tradition was continued without any interruption by Khyzyl storytellers until the 1970s. Among the last great ones were Semyon Kadyshev (1885-1977), who lived among the Khaas people near Lake Shira, and brother and sister Pyotr Kurbizhekov (1910-1966) and Anna Kurbizhekova (1930-1990), who lived along the Üüs river.

Prose stories, which are called “kip-chookh”, are told by women as well as men and include sacred myths about the origin of the world, creator spirits, spirit owners and other supernatural spirits; stories and legends about historical heroes, shamans, ancestors of the tribes; as well as humorous tales and fairytales. The most comprehensive kip-chookh stories, just like alyptygh nymakh stories, “epic with a horse”, include songs, dirge songs, and laments.

Epics (stories) and singing were accompanied by string instruments. In this way, the gait of a horse was imitated, or the adventures of a hero were being emphasized. Hunters used various wind instruments to imitate animal calls and thus attract the desired game. When people played flutes, string instruments or the jew’s harp, it was mainly for personal entertainment. They improvised on standard melodies, or they spontaneously created their own melodies, being inspired by the sound of the environment or closer surroundings.

Such rich creativity is awarded by a supernatural source, conveyed in the dreams of the people. Such gifts and talents are handed down in a line (family) and on the basis of their ancestors. Men and women alike are supported by spiritual powers, which are independent but, however, still responsible for the epics performed in throat singing. These spirits protect and support the “khaijy”, the storytellers of epics, and takhpakhchy, the singers of improvised songs.

Traditional vocal techniques

- Khai (throat singing – guttural singing)

Khai (or kai, as it is called among the Altaian and Shor people) is the traditional form of overtone singing from the north-western Sayan-Altai region, with only the highest and lowest vocal registers being used. It is largely a male vocal technique, though women are known to have performed and to perform it as well. It is inextricably linked with heroic storytelling, epics with a hero / heroine; it is in high esteem and constitutes an important part of the cultural heritage.

Throat singing and overtone singing is a common feature of all southern Siberian Turkic, many Mongolian, as well as some Kazakh peoples. It is also performed by many Turkic tribes in Central Asia. Overtone singing is a very special technique, wherein a single vocalist produces simultaneously two distinct tones. In its clearest (Tuvan and Mongolian) form, one tone is a low fundamental pitch that is sustained like a drone, while the second is a series of flutelike harmonics that resonate high above this drone. A real master may amplify the overtones at the expense of the fundamental pitch, even to the point that the drone becomes inaudible. Another technique often used combines a normal glottal pitch with a low-frequency pulse-like vibration, known as vocal fry. Texts are usually sung in such a vocal fry of about 25-20 Hz. The Shor and the Khakas people do not usually sing their texts in such a fundamental pitch, as they use kharygha more sparingly.

Unlike the Tuvans and the Mongolians, the more northern located Khakas, Altai and Shor people do not express the overtones very much in their khai or kai. Khai is produced by generating a fundamental tone while pressing the diaphragm and slightly pressing together the vocal cords. In this way, a hoarse sound arises, accompanied by soft overtones that change with the vowels of the recited text, thus creating a multi-layered sound hovering above the basic drone. Primarily, the epics are performed together with a string instrument. In the Khakas tradition, however, the overtones are rarely used to create a melody. Khai is not used to show virtuosity, but rather to convey texts in a convincing way; for this reason, this is only rarely performed independently. By using the technique of khai, the storyteller clearly emphasised the text, while at the same time making overtones subtly resonate above the recited text. The overtones help to reinforce the story’s text, as they create an extraordinary timbre texture that brings about the supernatural time-space feeling, in which the epic world and the story come to life.

- Kharygha, kharghyra (from khorlirgha, the Khakas word for snoring) or ulugh chon khai (“khai of the respected elders”) is the lowest sound a human voice can generate. This sound is related to the Altaian karkyra and the Tuvan kargyraa. It rises from the deepest part of the trachea and resonates in the chest. It is used for short episodes in heroic epics.

- Küülîp or küveler means “humming” and sounds an octave higher than kharygha. It is related to the Altaian köömöi, the Tuvan khöömei, and the Mongolian khöömii, but focuses less on producing discernible overtones. It is the main style for storytelling. This style is often simply called “khai” because it is the only style that has survived the Soviet period.

- Syghyrtyp means “to whistle”. This is a style of overtone singing, wherein there are generated tones in the throat that are comparable with the wailing sounds of the wind. Overtones are created between cavity, pharynx and tongue. This style is related with the sygyt of the Altaian and Tuvan people, wherein the highest and brightest tones are generated as the highest register of the voice is used. (In nature, every single tone and sound has overtones; even the wailing of the wind has its overtone vibrations). Whistling is only sparingly used; it is only used for short melodies at the end of phrases; humming (küülîp) is followed by whistling.

The old performers mostly used küülîp to perform stories and songs. Performers today use khai (overtone) mainly for songs and, to a smaller extent, for prayers. Kharygha and syghyrtyp are as frequently used as küülîp.

|

|

Instruments:

|

|

– aghas-khomys – aghas-khomys

|

- Khomys (string instument)

This is a two-string or three-string lute, related to the Altaian topshur, the Tuvan doshpulur and the Mongolian tovshuur.

The Khakas people play two types of khomys: the aghas-khomys and the topchyl-khomys. Both have a body and neck carved from cedar wood, but while the former has a wooden sounding board from cedar wood, the body of the latter is covered with the skin of wild roe deer, domestic goat, or cattle. The traditional stringing is of twisted horsetail hair, and the strings are tuned a fourth or fifth apart; the three-string khomys is tuned a fourth plus a fifth apart.

– topchyl-khomys – topchyl-khomys

|

|

- Yykh (string instrument)

This is a two-string fiddle of the Khakas people, related to the Altaian ikili, the Tuvan igil and the Mongolian ikil.

Its body is similar to the khomys but has a longer neck. The body, like that of the topchyl-khomys, is covered with the skin of wild roe deer, domestic goat or juvenile cattle. The strings are made from twisted horsetail hair and are tuned a fourth or fifth apart. It is played with a bow made of willow branch with horsetail hair stringing, and it is coated with larch or cedar wood resin.

|

|

- Chatkhan or chadyghan (string instrument)

The chatkhan is the most prominent instrument of the Khakas people. It is a plucked long box zither with six to fourteen strings, distantly related to the Tuvan chadagan, Mongolian yatga, Japanese koto, Chinese quin and Korean kayagum.

The Khakas zither is a 1.5 metres long box from spruce wood, with each metal string running over an individual movable bridge made from sheep’s knucklebone. It is likely to originally have consisted of a short body (about 50 cm long) hollowed out from underneath like an upturned trough, with strings of horsetail hair.

However, in the 18th century it already broadly had its present shape: a long box of nailed boards with 6 or 7 metal strings. It has a rather smooth sound, ideal for performance in intimate company. The chatkhan is tuned in a pentatonic scale, with one or two strings tuned a fifth and/or octave below the lowest melody string, to obtain a drone. Some strings are also pressed to the left of the moveable bridge with the left hand, to raise the pitch. The strings are plucked and strummed to the right of the moveable bridges with the right hand to produce both melody and drone. The left hand is used to press particular strings to the left of the moveable bridge. In this way, diatonic melodies can be played on the pentatonic instrument, as well as the adorning gliding tones and vibratos so typical for the instrument.

Unlike the long zithers (yatga) of the Mongols, who mainly used the long zither at court and in monasteries since strings symbolised the twelve levels of the palace hierarchy, the chatkhan was used to accompany lyrical, historical and epic stories and heroic tales in intimate gatherings of common people, especially at weddings and nocturnal dead wakes.

The chatkhan (like the Khakas lutes) could hold a spirit, and therefore handling and playing was bound by taboos and rituals.

|

|

- Khobyrakh or Shoor (wind instrument)

Formerly an open end-blown flute similar to that used by the Bashkirs and the Caucasians. It was a 30 to 65 cm long, smooth, hollow pipe without finger holes, made of the stem of a large umbelliferous or willow cut on the spot. The Khaas tribe called it “khobyrakh” (lit. “hogweed”, a kind of umbelliferous), while the Saghai and Shor tribes called it “shoor”, like the Altaians, who locally also call it "shagur" or "komurgai" and which is similar to the shoor and the khobyrakh. It has, however, holes at the side and is made from wood. Its length is 30-40 cm.

Nowadays it has a small block with a slit at the top, six finger holes, and it is made of wood veneer (ash, mahogany and other species) or plastic.

|

chervil

|

- Syylas (wind instrument)

An open end-blown flute similar to that used by the Bashkirs and the Caucasians. It is bigger than the khobyrakh (60-80 cm long) with four finger holes to the front and one to the back. It is made from the stem of the big chevil (parasol-like plant, designation for big umbelliferous plants) or from wood. Today it is mostly made from plastic.

Melodies are created via airflow by covering or uncovering the lower end, using a finger. As such a traditionally produced instrument is unsuitable for transport, rather fragile and frail, this instrument is nowadays made from plastics. Today, it often has 3 and sometimes even 6 fingerholes.

chervil

chervil

|

|

- Tüür - single-sided frame drum – shaman’s drum (tungur) – (percussion instrument)

The drum consists of a round wooden frame fixed inside with one vertical and one horizontal wooden stick and covered with the skin of a cloven-hoofed animal. Formerly it was only used as a ritual instrument by shamans (kham). Today it is also used as the main percussion instrument in music ensembles.

When used as a ritual instrument, drawings are made on the outer side of the drumhead, and coloured ribbons (chalama), metal bits and bells are attached to the horizontal stick inside. It is beaten with an orba, a drum stick made of wood and leather.

- Orba – drum stick

It is made of the urinary bladder of an animal filled with grain and has a handle.

|

|

- Khongyros (percussion instrument)

Made of leather and filled with grain. |

|

- Sangyros (percussion instrument)

Rattle with metal rings; ornamented with horse and ram head. |

|

- Khazykhtar (percussion instrument)

Rattle of sheep knucklebones. |

|

- Sang (percussion instrument)

Iron hand bell with a wooden handle in the shape of an ibex. |

|