|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

|

1. Obulo bwaffe - Buganda region - 8:58

2. Kiyiri omulangira - Buganda region - 6:37

3. Lwaki etooke liyitibwa etooke - Buganda region - 4:22

4. Amaaka gaguma - Banyankore region - 5:55

5. Kaleeba - Buganda Region - 5:08

6. Enyonyi muzinge - Buganda region - 3:47

7. Ekirum’ente - Bunyoreo region - 12:40

8. Lwaki enkoko etakula - Buganda region - 4:31

9. Nsangi - Buganda region - 7:36

10. Nkalabanda - Buganda region - 4:50

11. Amawugulu - Buganda region - 5:01

Traditional music of the Bantu women and folktales of the Baganda women

Africa is inhabited by different ethnic groups, each with a musical tradition of its own. This is a rich traditional music heritage that has been orally transmitted from generation to generation for centuries. Despite external influences, the majority of these ethnic groups continue to value and practice their respective traditional musical styles, which in turn have to establish strong musical and cultural identities and continue to do so.

Ugandan music is generally rhythmic and the complexity of these rhythms varies due to the difference between the ethnic groups. These differences are also reflected in the varied instrumentation. African music is usually pentatonic, but a few tribes also use a hexatonic scale. Most of the Ugandan vocal music is accompanied by traditional instruments. The literature embedded in vocal music is purposely meant to transform the social communities, i.e. in their structural adjustment.

Although Uganda is inhabited by a large variety of ethnic groups, a broad linguistic division is usually made between the Bantu-speaking majority, who lives in the central, southern and western parts of the country, and the non-Bantu speakers, who occupy the eastern, northern and north-western part of the country (these may be sub-divided into Nilotic and Central Sudanic peoples).

The Bantu people

The word Bantu itself, incidentally, simply means "human beings". These tribes all have Bantu as a core language in common, while their own languages usually comprise many dialects and variations. The ethno-linguistic Bantu group is most commonly said to have its origins in Western Africa (Cameroon). The Bantu came from Central Africa, from where they began to expand to other parts around 2000 BC. These migrations are believed to have been the result of an increasingly settled agricultural lifestyle: although needing little land (far less than herding cattle use), land had to be fertile and well watered for cultivation to be a viable alternative. Population pressure in Central Africa may therefore have prompted the first Bantu migrations.

Bantu-speakers had entered southern Uganda probably by the end of the first millennium A.D. and they had developed centralized kingdoms by the fifteenth or the sixteenth century. Their languages are classified as Eastern and Western Lacustrine. The Western form comprises the area surrounding East Africa‘s Great Lakes (Victoria, Kyoga, Edward, and Albert in Uganda). To the Eastern group belong the Baganda people (whose language is Luganda), also included are the Basoga, the Bagisu people, and many smaller societies in Kenya, Tanzania, and at the Zambezi River where the Monomatapa kings built the famous Great Zimbabwe complex.

Movements by small groups from the Great Lakes region to the southeast were more rapid, with initial settlements widely dispersed near the coast and near rivers, due to comparatively harsh farming conditions in areas further away from water. Pioneering groups had reached modern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa along the coast by 300 AD, and the modern Northern Province (formerly called the Transvaal) by 500 AD. It is not clear when exactly the Bantu had moved into the savannahs to the south, in what are now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, and Zambia. Such processes of state formation occurred with increasing frequency from the 16th century onward. They were probably due to denser population, which led to more specialized divisions of labour, including military power, while making emigration more difficult, further due to increased trade among African communities and with European and Arab traders and the Coast people (Swahili) along the coasts (Indian Ocean), with technological developments in economic activity, and new techniques in the politicalspiritual ritualization of royalty as the source of national strength and health.

The Bantu expansion was a millenia long series of physical migrations, a diffusion of language and knowledge out into and in from neighbouring populations, and a creation of new society groups involving inter-marriage among communities and small groups moving to communities and small groups moving to new areas. Bantu speakers developed novel methods of agriculture and metalworking, which allowed people to colonize new areas with widely varying ecologies in greater densities than huntergatherers, the homeland people (original habitants of these regions). Meanwhile in eastern and southern Africa, Bantu speakers adopted livestock husbandry from other peoples they encountered, and in turn passed this form of living on to hunter-gatherers (San people), so that herding reached the far south several centuries before Bantu speaking migrants did. The linguistic and genetic evidence of all this supports the theory that the Bantu expansion was one of the most significant human migrations and cultural transformations within the past few thousand years in Africa.

Several successive waves of migrations over the following millennia followed on the tracks of the first. They were neither planned nor instantaneous, put took place gradually over hundreds and thousands of years, allowing plenty of time for Bantu culture to spread and be influenced by other cultures it came in contact with, either through assimilation or - rarer, it seems - conquest. Bantu culture most likely reached from the west, and possibly the south, some time between 200-1000 AD, having passed through what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). By 600 AD they had dispersed over enormous areas, covering what is now Tanzania and Mozambique on the East-African coast, south as far as the southern African coast and west into parts of Angola. The result of all this migration and integration was the development of more than five hundred Bantu-related languages sprinkled around this area of Africa.

The history of the Bantu migrations itself is some what confused, last but not least because the on-going process of fusion and mutual influence with neighbouring peoples meant that the tribes we know today did not actually emerge as distinct groups until about five hundred years ago at the earliest. And as the Bantu people met and absorbed other peoples, they also adopted some of the assimilated peoples‘ histories and traditions.

As cultivators, the Bantu sought out abundantly watered areas, often in the highlands, and they were the first to start large-scale forest clearance for cultivation, with the result that even today many Bantu areas suffer enormous losses of topsoil each year through erosion. Although the new-comers were frequently displaced, and though they sometimes fused with previous Bantu immigrants, Cushitic peoples (from whom some pastoral practices were adopted) or the hunters and gatherers they came in contact with, the essence of the Bantu identity remained the same, namely the reliance on agriculture, and hence a relatively settled way of life. Other Bantu cultural elements that have survived, and not just in Kenya, are cosmological beliefs, such as the belief in a single creator god, and, further, the belief in the survival of ancestors as spirits or intermediaries between the living and god.

The Gusii, Kuria and Luhya of Lake Victoria are the descendants of possibly the earliest Bantu groups to have arrived and are believed to have introduced iron smelting and the use of iron tools to the region. Although it is obvious that the Bantu must have moved north to populate the areas they cover today in Uganda and Kenya, the oral legends of the central highlands Bantu invariably point to the north - usually the Nyambene Hills which lie north of Mount Kenya - as their place of origin (ie. some five hundred years ago). From there, as their oral histories say, the ancestors of the present-day Kikuyu, Meru, Embu, Chuka and Kamba, and possibly others as well, migrated south into the foothills of Mount Kenya itself, where they eventually dispersed to their present locations. This would indicate that once in Kenya, the Bantu headed much further north than their present territories, and were pushed back by either the Nilotics or Cushites. This theory is backed-up by other oral histories which state that the central highlands Bantu came not from the north or west, but rather from the Indian Ocean coast to the east. The coastal Bantu themselves – the nine tribes‘ of the Mijikenda, together with the Pokomo – are unanimous in that they came from a semi-mythical place called Shungwaya in the north, which is likely to have been in what is now Somalia.

- more information about see: Uganda the country and the people - Bantu tradition

Folktales

Folktales define community; reflect the history, traditional values and accumulated wisdom. Every culture has its own collection of ancient and traditional stories that have been orally transmitted from generation to generation.

Baganda women told these stories to the children in the evening after work and before they had to go to bed around a fire. In some of the stories, general animals, birds and plants have human characteristics (souls), by means of which they talk and develop relationships with humans. They have a supernatural element which allows them to perform tasks only in folktales.

Stories have always been very significant to the tradition and the culture of Buganda. The young generation has been taught about the past of their kingdom, they have learnt about their ancestors, cultural taboos, history, values of life, etc.

Traditionally, the stories or legends were a main source of education in the African life style, that involved participation, which was oral and it was the way to teach the young ones to used and to know almost everything about their culture, people and historical background.

Traditional storytellers (Bards and Griots)

The ancient oral tradition of storytelling by the bards or griots still exists. Each people has its very own term for this highly refined and deeply spiritual discipline, as these artists are masters in reciting epics and many other stories. The power of these storytellers is breathtaking, and they guide through the experiences of life of most people. It is a privilege to have seen such still unbroken living tradition, which has survived for thousands of years and has nothing in common with the modern revival of storytelling (songwriters). Their roles are often as spiritual teachers for whom the stories and music become a medium as well as historians and traditionbearers. People today are rediscovering this oral tradition with all its wisdom, with the pleasure of telling stories about the people‘s actual life and roots (songwriters).

The traditional African storytelling was performed within the community. In African societies everyone participates in formal and informal storytelling as an interactive oral performance — such a form of participation is an essential part of traditional African communal life and constitutes the basic training in a particular culture’s oral arts and skills. These are performed in an interactive „call-and-response“; and everywhere in Africa it is the soloist who „raises the story (the song line)“, and the community brings the chorus responding, or „will agree during the song.“

There are stories that have been drawn on the walls of caves and which were depicted in rock paintings in early times (e.g. San people in South Africa). Painted stories were used to explain the power of nature that normal humans did not understand und had to be translated into the form of stories. There are also stories that tell about the creators, gods and heroes; stories that reminded people of behaviour that was good and would be helpful for others, of the taboos, as well as of behaviour that was evil and not to be accepted. These stories have a basic theme or message that has been passed down through generations.

There are two kinds of storytellers in Africa. The best known are griots, who come from West Africa. Griots are historian tellers, praise-singers and musical entertainers who know the entire history of families, the struggles of them and their ancestors; they know who married whom, when and where, and they know all the children born. They also tell the stories of entire villages – tales of feast and famines, tales of prosperity and destruction, tales of good times and bad times. They perform great annual celebrations where there are large gatherings of people to celebrate this special occasion or to perform ceremonies. In West Africa anybody who wanted to be a griot had to be born into a family of griots. The knowledge is passed down from parents to children. In some tribes, such as the Malinke from Mali, the griots are part of a caste, a separate social group. Members cannot marry outside their caste.

The second kind of African storytellers performs in everyday places, such as the marketplace, at festivals, or at family parties. These storytellers sometime wear hats, or they display story nets on which such things as a bone, a skull, or a rattle are hung. Each item represents a story that can be told.

African storytelling and orature are highly skilled performance acts in art. These living traditions continue to survive and to adapt to the challenges of modernization characteristic for today‘s Africa, and they have fused, in uniquely African ways, in newer forms, and with all these influences they enrich the global human experience and its creative expressions around the world. In modern times such epic forms and theatre groups are even used when lecturing children; thereby the children are stimulated to participate and the stories become experiences to be made by all of them.

Songs of the Baganda people

The Baganda people make up the largest ethnic group in Uganda, though they represent only 16.7 per cent of the population. (The name Uganda, the Swahili term for Buganda, was adopted by British officials in 1884 when they etablished the Uganda Protectorate, centered in Buganda).

They speak a Bantu dialect called Luganda belonging to the Niger-Congo family. Like many other African languages, it is a tonal language which means that some words are differentiated by means of pitches. Words that are spelled in the same way, however, have a different meaning. It is a language that is rich in metaphors and proverbs.

Buganda is located in central Uganda and it is a region of the Baganda people. Its nucleus is Kampala city. Buganda‘s boundaries are marked by Lake Victoria in the^south, the Victoria Nile River on the east, and Lake Kyoga on the north. The kingdom comprises 52 clans. At present it is the largest of the traditional kingdoms.

Their music is mainly slow with more emphasis on a regular meter. It is composed of contrasted lyrics and yodles (flactuating vocal lines). Since they are the origin of the Negro people, they have a huge variety of song forms such as; lullabies, historical songs, work songs, ceremonic songs, praise the kings (royal songs), wedding songs, etc. Their scale is purely pentatonic. Most of the vocal lines are in a responsarial form, solo form and chorus form. Since these songs are vocal dominant, they are basically meant to deal with social transformation. Funerals are major ceremonial and social events.

The Baganda passes through the stages of omwana (child), omuvubuka (youth), and omusajja or omukazi (man or woman). After death one becomes an omuzima (spirit), and the Baganda also believe in rebirth (reincarnation). After birth, the umbilical cord is retained for later use in a ceremony called Kwalula Abaana. During this ceremony the child gathers with other members of the father‘s clan to receive his/her name. Boys and girls are expected to conform in their behaviour to what the Baganda refer to as mpisa (manners). This includes being obedient to adults, greeting visitors properly, and sitting correctly (for girls). Sexual education for females

is more systematic than it is for males. The father‘s sister (Ssenga) is the most significant moral authority for girls. Grandmothers instruct girls soon after their menstruation, during a period of seclusion, about sexual matters and future domestic responsibilities. Marriage and the birth of children are prerequisites for adult status. Women typically wear a busuuti. This is a floor-length, brightly coloured cloth dress with a square neckline and short, puffed sleeves. The garment is fastened with a sash placed just below the waist over the hips, and by two buttons on the left side of the neckline. Traditionally, the busuuti was strapless and made from bark-cloth. The busuuti is worn on all festive and ceremonial occasions. The indigenous dress of the Baganda men is a kanzu, a long, white cotton robe. On special occasions, it is worn over trousers with a Western-style suit jacket over it.

|

|

Busuuti –

children rests on the mothers back for mobility |

Kanzu –

with a Western-style suit jacket |

|

The bark from a species of fig trees called mutuba is soaked in water, then beaten with a wooden mallet. This yields a soft material that is decorated with paint and then cut into strips of various sizes. Larger strips traditionally were used for partitions in homes. Smaller pieces were decorated with black dye and worn as clothing by women. They have been replaced by the cotton cloth Busuuti. Bark-cloth is found today as decorative placemats, coasters, and design on cards of various sorts.

|

The staple food of the Baganda is matooke (a tropical fruit of the banana family). It is steamed or boiled and commonly served with groundnut (peanut) sauce or meat soup. Furthermore, they live on eggs, fish, beans, groundnuts, beef, chicken, and goats as well as termites and grasshoppers according to the season. Common vegetables are cabbage, beans, mushrooms, carrots, cassava, sweet potatoes, onions, and various types of greens. Fruits include sweet bananas, pineapples, passion fruit, and papaya. Drinks made from bananas (mwenge), pineapples (munanansi), and maize (musoli). Baganda have cutlery, but most prefer to eat with their hands, especially at home. Their homes are usually made of wattle and daub (woven rods and twigs plastered with clay and mud). Generally, they have thatched or corrugated iron roofs. More affluent farmers live in homes constructed of cement, with tile roofs. Cooking is commonly done in a separate cooking house over an open wood fire. The traditional term for marriage was jangu enfumbire (come, cook for me). After the wedding, a new household is established, usually in the village of the husband. The husband and father was supreme. Children and women knelt in front of the husband in deference to his authority, and he was served his food first. Basketry is still a widespread art. These mats are colourful and intricately designed. Most Baganda are peasant farmers who live in rural villages. Rich red clay on hillsides, a moderate temperature, and plentiful rainfall combine to provide a good environment for the year-round availability of plantain, the staple crop, as well as the seasonal production of coffee, cotton, and tea as cash crops.

Traditional Dances - Every tribe in Uganda has at least traditional dances. For example „Baakisiimba, Nankasa, Muwogola“ is a traditional dance that originated in the palace of the Buganda Kingdom. The Kabaka‘s Palace was a special place where royal dancers and drummers regularly performed. Dancing is frequently practised by all, beginning already in early childhood.

Riddles, myths and legends tell about the origin and history of the Baganda as well as the work of the real world. The most significant legend involves Kintu, the first Kabaka (king). He is believed to have married a woman called Nambi. Walumbe (Death) brings illness and death to children and then adults. Up to the present day, Death has lived upon the earth with no one knowing when or whom he will strike.

The Buganda believed in superhuman spirits. Balubaale were men who carried over into death. Mizimu were the ghosts of dead people. They believed that the soul still exists. The supreme power was the Creator, Katonda.

Some other Balubaale (about 37) had specific functions; there were the god of the sky, god of the rainbow, god of the lake, etc. They built for them all special shrines or temples. Temples were served by a medium or a priest who had powers over the temple. They also believed in spiritual forces, particularly the action of witches, who were thought to cause illness and other misfortune. People often wore amulets (charms) to ward off their evil powers. The most significant spirits were the Muzimu or ancestors who visited the living in their dreams and sometimes warned of impeding dangers. The Balubaale cult no longer exists. The belief in ancestors and the power of witches, however, is still quite common.

Each of the clans had a totem, which may not be eaten by a clan member, including: grasshoppers (nsenere), lungfish and one variety of beans. Ritual food: Food which was associated with feasts and celebration: Matooke (cooking banana), sesame, mushrooms, chicken and some fish have played an important role in the celebrations of the Kiganda. Presents and gifts in the form of dowry were typical for weddings, also the ceremony for naming a child, especially on the occasion of the birth of twins.

- more information about Baganda people see: Uganda the country and the people - Bantu tradition

1. Obulo bwaffe - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, adungu (bow harp)

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, adungu bass

Birds sing and argue like human beings.

- They have a message for the elder of the village community, they advise them to be careful with their children. If we are a bad role-model for our children and if we assign them tasks not suited for them yet, this does not guarantee that we educate and raise them well, especially if one member of the family is not present.

2. Kiyiri omulangira - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, engoma (Uganda drum)

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, amadinda (xylophone)

It may sometimes be dangerous to accept offers from strangers, especially if the gift offered is something edible.

- The story tells how a girl survives because she is well-educated. She does not eat the piece offered to her but rather keeps it. If he changes his mind and wants to have his present back, she can give it back to him. If it has, however, rotten in the meantime, because it has not been eaten, she has to bear the consequences.

3. Lwaki etooke liyitibwa etooke - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: akadongo kabaluru (thumb piano)

The banana (tooke) became the staple food in the Kingdom of Buganda.

- A very long time ago, the king found out that he liked the taste of the banana juice as, after a while and due to fermentation, it tastes like alcohol.

- There are various sorts of bananas and also ways for their use: the plantain, the „bogoya“, becomes „ndiizi“, when it is ripe; and from „ndiizi“, there is made banana beer, or they are also cooked - „kivuuvu“; the plantain „matooke“ is served with peanut butter sauce.

5. Kaleeba - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, endingidi (one-string-fiddle)

Hard work and a will of iron will not always be crowned with success. Also all we wish for and think of cannot always come true. Concentration and determination, however, may help us to achieve our goals, but only after we have defeated everything else.

6. Enyonyi muzinge - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, adungu (bow harp), drum

Elder people and also our parents will always try to give us good advice, and we children are raised on the basis of such experiences. We do, however, not always behave the way we were taught to behave. We do not stick to what we have learned. We live up to our curiosity and try things others have warned us about. This may, however, result in a dangerous situation.

8. Lwaki enkoko etakula - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: akadongo kabaluru (thumb piano)

When chicken move backwards while searching and scratching the ground, they are still moving forwards.

- In Buganda the children are told that they look for the needle the duck has lost.

- In the country, they are a good example for the community. When the cock crows early in the morning, this tells all to get up and start with their work.

9. Nsangi - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, endongo (lyre)

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, drum

It is rather dangerous when the community spoils a child and thus raises it badly.

- The story tells what happens when such a spoilt girl grows up and wants to get married and have its own family, especially if its parents have then already died and cannot intervene and help anymore.

10. Nkalabanda - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and male voice

- Israel Kalungi: akadongo kabaluru (thumb piano)

The education and teaching of children will be in the hand of the parents or the elders within the community.

- This story explains what happens when a child leaves its parents’ home and wants to have its own family.

11. Amawugulu - Buganda region

- Sarah Ndagire: text and female voice

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, engalabi (long drum))

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, engoma (Uganda drum), ensaasi (shakers)

The Baganda believe that an owl* announces the death or upcoming death of someone in the family or in the village.

- In this song there is told how a female singer tells the community about the role the owl has within the community, that it announces death – no matter where it is.

- If the people of the village find an owl near their homes, this causes an uproar, and the animal is driven away with torches.

* (For the Bantu, an owl also stands for a fortune teller or wizard with magical powers.)

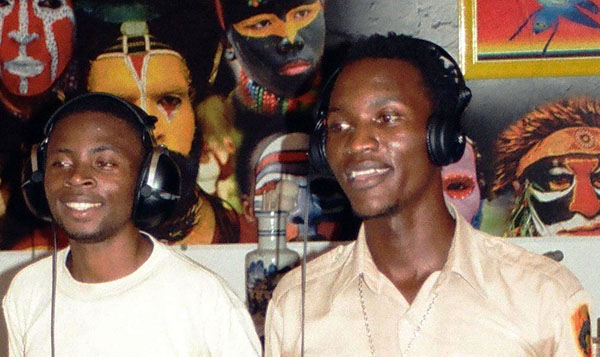

Lawrence Lubega - Israel Kalungi

Songs of the Banyoro people

The people of Bunyoro are known as Banyoro (singular Munyoro). They belong to the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara in western Uganda, in the area to the immediate east of Lake Albert. Their cultural leader is the Omukama (king). Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom is the districts of Hima, Masindi and Kibale. The native language is Runyoro-Rutooro, a Bantu language. Runyoro-Rutooro is also spoken by the people of Toro (Batooro) Kingdom, whose cultural traditions are similar to those of the Banyoro.

They were polygamous, and the dowry was often paid after several years of marriage. Death was usually attributed to sorcerers, ghosts and other non-human agents. Death was the result of action on the side of bad neighbours, provided with a vast range of magical and semi-magical means of injuring and even killing others. Indeed, many deaths were attributed to the act of sorcery by ill-wishers. They celebrated the new moon and an annual ceremony called „Empango“. The basis of the kingdom was the family head „Nyineka“. Each village had an elder chief known as „Mukuru w‘Omugongo“.

Guests were always welcome and always regaled with something, even if they arrived after midnight. Their craftsmen were also very talented, and there was a flourishing trade in durables with the regions outside the kingdom. The blacksmiths working metal were also well-respected, especially for their production of hoes for the cultivation of the fields.

The melodies are based on a constant meter with two distinctive rhythms (runyege and entongoro). Their vocal lines are characterised by massive yodelling (melismatic lines). Their music is mainly responsorial in nature. They are the origin of Bushmen and Negro people, and their music is clearly pentatonic. At times, their vocal lines are polyphonous.

- Runyege / Entongoro dance* -This is a ceremonial dance from Bunyoro and Toro (Batooro) Kingdom. It is also a courtship dance performed by the youth when it is time for them to choose partners for marriage. The dance was named after the rattles (ebinyege - binyege - entongoro) that are tied on boys‘legs to produce percussion - like sound on rhythm. The sound produced by rattles is more exciting as it is well syncopated as the main beat is displaced but everything blending with the song and drum rhythms.

Once upon a time, there was a problem in the Kingdom when over 10 men wanted to marry the same beautiful and good-looking girl. What happens is that a very big ceremony is organized and all the male candidates have to come and dance. The girl had to choose the best male dancer. In this culture it is believed that the best dancers also show the best marriage life. It is also to see who is the strongest among the men as families in Africa do not want to give their beautiful girls to weak men, for when there is a period of drought or famine, one should have a husband who will really struggle to see that he looks for water and food. So in this dance the man who gets tired first, loses first and that who dances till the end wins the game. There was a problem when some girls wanted to get married to particular men and these were the men who got tired first – what a pity! The girls did not have a choice, as their parents decide for them whom to marry.

The western Lacustrine Bantu people includes the Banyoro, Batooro, and Banyankore: their complex kingdoms are believed to be the product of acculturation between two different ethnic groups, the Hima and the Bayira. The Hima are said to be the descendants of pastoralists who migrated into the region from the northeast. The Bayira are said to be descendants of agricultural populations that preceded the Hima as cultivators in the region. Bunyoro region lies in the plateau of western Uganda, constituting about 3 per cent of the population. Its nucleus is Masindi and Hima. The Batooro region evolved out of a breakaway-segment of Bunyoro that split off an unspecified time before the nineteenth century. The Batooro and Banyoro speak closely related languages, Rutooro and Runyoro (a Bantu language), and they share many other cultural traits. The Batooro live on Uganda‘s western border, south of Lake Albert and constitute about 3.2 per cent of the population. In pre-colonial times, they lived in a highly centralized kingdom like Buganda, which was stratified like the society of Baganda people.

- more information about Banyoro people see: Uganda the country and the people - Bantu tradition

7. Ekirum'ente - Bunyoro region

- Sarah Ndagire: lead voice, yodelling, ullulation

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, endege (ankle bells)

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, engoma (Uganda drum), engalabi (long drum), endege (ankle bells)

A traditional marriage song from Bunyoro which brings us through all stages of the wedding, from the beginning to the end of a traditional wedding.

– *Runyege / Entongoro dance“ - This is a ceremonial dance from Bunyoro and Toro (Batooro) Kingdom. It is also a courtship dance performed by the youth when it is time for them to choose partners for marriage.

Songs of the Banyankore people

Their vocal music is characterised by old type poetry recitals which in many cases signfy bravery, elongated vocal lines in imitation of the mowing cattle. Their vocal melodies are mainly responsorial in nature and at times polyphonous.

The Ankole region, also referred to as Nkole (Nyankore), is one of the four kingdoms in Uganda. It is located in the southwest of Uganda to the west of Lake Edward. They inhabit the districts of Mbarara, Bushenyi, and Ntungamo. People from the Rujumbura and Rubando tribe in the Rukungiri district share the same cultural background. The Ankole people was usually known as Kaaro-Karungi, and the expression Nkore is said to have been adopted during the 17th century following the devastating invasion of Kaaro-Karungi by Chawaali, the then Omukama (king) of Bunyoro-Kitara. The word Ankole was introduced by the British colonial administration to describe the greater kingdom which was formed by adding to the Nkore realm the former independent kingdoms of Igara, Sheema, Buhweju, and parts of Mpororo.

It is ruled by a monarch (mugabe = king). The Banyankore people also belong to the Bantu groupe and are great cattle keepers. They breed long white-horned cows that give beef, milk and other products and are most prestigious for the farmers. The breeders are so proud of their cattles, so that they own them in large numbers and these animals exert great influence on their daily life routine, especially in rituals, music and dances. Many songs are about cows. Poetry comprises songs that tell of men who own large herds, tell about their individual abilities and their special tradition in authorities within the society; brave, wealthy, great warriors and owners of beautiful women.

For the women and the female children over 6 years it is forbidden to eat eggs, chicken, and pork and to drink goat‘s milk. Fish was even a taboo for all members of this tribe. The Bahima have numerous taboos in regard to drinking milk. It is not allowed to drink milk and at the same time eat something, as milk must not come together with other food in a person‘s stomach.

According to legend, the creator Ruhanga came down to Earth and settled here. He was also their principal god and hence worshipped. He was asked for advice in case of problems, or the people used magic or even black magic to solve their problems. Each family also had their own gods they also worshipped and gave sacrifices to. It was common practice to erect special family shrines. Death itself was not seen as a natural consequence but rather as a result of magic: people were bewitched and therefore died. According to their tradition, death was attributed to sorcery, misfortune and the bad influence exerted by the spirit of the neighbours. They even had a saying, „Tihariho mufu atarogyirwe“, meaning “There is nobody that dies without being bewitched”. They found it hard to believe that a man could die without his death being the result of witchcraft and malevolence of other persons. Accordingly, after every death, the family would consult a witchdoctor to detect whoever was responsible for this person’s death.

The deceased stayed in the house until all the important relatives had gathered. Among the Bayiru, the deceased would be buried in the compound or in the plantation. The Bahima would be buried in the cattle kraal (cattle bawn). Burial was usually done in the afternoon, and the bodies were buried facing towards the east. A woman was to lie on the left side of her husband. For women was accorded three days of mourning, and for a men four days. During the days of mourning, all the neighbours and relatives of the deceased would camp and sleep in the home of the deceased. During this period, the whole neighborhood would not dig or work; it was believed that if anyone dug, or did manual work, it would be his fault that the whole village be ravaged by hail storms. Such a person could also be regarded as a sorcerer. However, the abstinence of neighbours from digging and manual work was meant to console the relatives.

- more information about Banyankole people see: Uganda the country and the people - Bantu tradition

4. Amaaka gaguma - Banyankole

- Sarah Ndagire: female voice, engalo (handclapping)

- Israel Kalungi: male voice, engalo (handclapping)

- Lawrence Lubega: male voice, engoma (Uganda drum), ensaasi (shakers), engalo (handclapping)

The song tells about the misery and misfortune of a girl who has no saying in the wedding agreement. According to the rituals (tradition), the parents decide on who is going to marry whom, and sometimes even without the girl knowing anything. The groom’s parents pay an appropriate bride wealth, and arrangements are made when the girls is taken away from her parents.

– Today, however, the boy and the girl plan and arrange the wedding themselves, without knowledge or assent given by their parents.

Lawrence Lubega - Israel Kalungi

Instruments

adungu bass

|

- Adungu, Adeudeu - bow harp - arched harp - string instument

The adungu is a nine-string arched (bow) harp of the Alur people of northwestern Uganda. It is very similar to the tumi harp of the neighbouring Kebu people, and it is also used by the Lugbara and Ondrosi tribes in this northwestern region around the Nile. The harp is used to accompany epic and lyrical songs, and it is also used as a solo instrument or within ensembles. Players of arched harps have had a high social status and are included in royal retinues. Nowadays they also play in churches.

The adungu consists of an arched neck, a wooden resonator (sound box) in which the neck is fixed, and a series of parallel strings of unequal lengths that are plucked. The strings are fixed at one end to the resonator and run at an oblique angle to the neck, where they are attached and tuned with pegs.

The first, second, and third strings are tuned in octaves with the sixth, seventh, and eighth respectively. In traditional music the instrument is tuned in a pentatonic (five-note) scale, but it can also be tuned in modern style to a diatonic scale.

|

|

- Endingidi - Adigirgi - tube fiddle - one-string-fiddle - string instrument

This instrument is popular in the Buganda, Busoga, Ankole, Kigezi, western Nile, and Acholi regions. It consists of a single string, which is attached to a flexible stick and will sometimes have a resonator. Unlike other single-string instruments, it is played with a bow.

|

|

- Amadinda - Embaire - Entaara - Akadinda - xylophone

The xylophone is a very popular instrument in the Bantu region. The amadinda and akadinda vary in size and number of keys, though both are tuned in an equidistant pentatonic scale. The keys are separated by either long sticks (among the Buganda) or

short ones and are placed on banana stems. The Bakonyo and Basoga use both short and long sticks. The keys are tied in place by threading a string through small holes in the wood.

|

|

- Akadongo (thumb piano)

Many different names exist for this instrument; kalimba, sansa, and mbira are the most common ones. It consists of a series of flexible metal or cane tongues of varying lengths fixed to a wooden plate or trapezoidal sound box. Nowadays the resonator is made of kiaat wood, and the tines are made of high-quality spring steel. The musician holds the instrument in both hands and uses his thumbs to pluck the slightly upturned free end of the tines. The number and arrangement of the tines, or lameliae, vary regionally. The instrument accompanies a repertoire of "songs for thought," or laments, sung by both men and women.

In Buganda the instrument is known as "akadongo kabaluru" or "little instrument of the Alur tribe" from the northwest Nile region.

|

Drums in African tradition bring the power that drives a performance. Music is not merely entertainment, but it is ultimately bound to visual and dramatic arts as well as the larger fabric of life. Drums may be used for "talking"; that is, sending information and signals by imitating speech. Many African languages are both tonal (that is, meaning can depend on pitch inflections) and rhythmic (that is, accents may be durational), giving speech a musical quality that may be imitated by drums and other instruments. Drumming music and dance are almost always an accompaniment for any manner of ceremony; birth, marriages, funerals.

|

- Engalabi - long drum - percussion instrument

This traditional drum has a head made of reptile skin nailed to a wooden sound body. The engalabi from the Buganda region has an important roles in ceremonies and in theater. It is called "Okwabya olumbe". This is the installation of a successor to the deceased, thus the saying in Luganda (in Buganda a Bantu dialect) "Tugenda mungalabi", meaning we are going to the engalabi, that is, long drum. Rule in playing the drum is the use of bare hands.

|

|

- Engoma - Empuunyi - Uganda drum - percussion instrument

Embuutu; big drum, Empuunyi; bass drum.

While larger versions of this drum are traditionally hand-carved from old-growth hardwood trees, now these drums are made with pinewood slats tied together like barrels. Smaller drums are laminated and turned on a lathe and may be provided with a rope carrying the handle. All these drums have heads made from hide held by hardwood pegs hammered into the side of the drum.

|

|

- Ensaasi - Akacence - Enseege - shakers - percussion instrument

Shakers are made in pairs from gourds or shells, sometimes with stick handles, and are used to accompany other traditional instruments in Uganda. The central and northern (Alpaa) regions have shakers that produce a continuous sound as beads move from side to side in the gourd or shell. Generally, these shakers produce sounds by many small objects, such as pebbles, rattling together inside the body.

|

Revised by Hermelinde Steiner

PageTop

|