- Uganda the country and the people - Bantu tradition

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2016

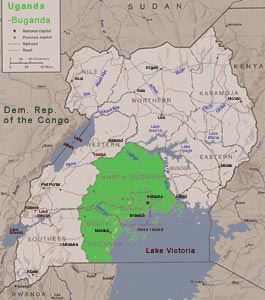

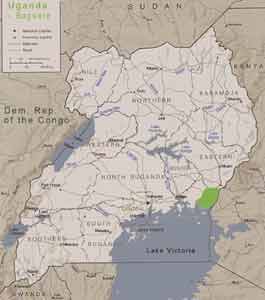

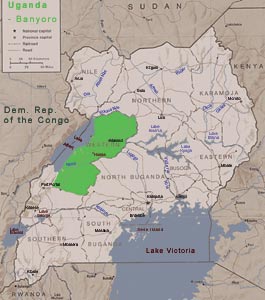

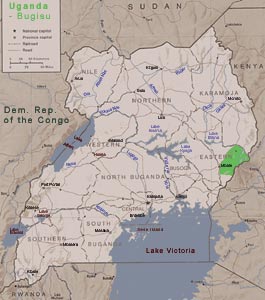

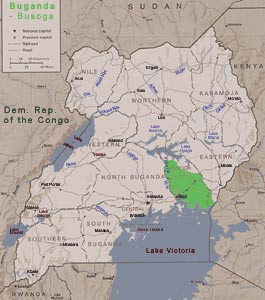

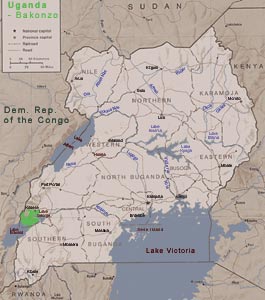

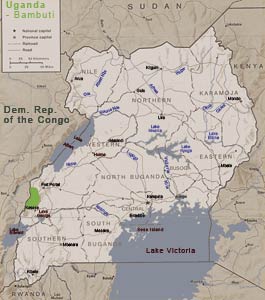

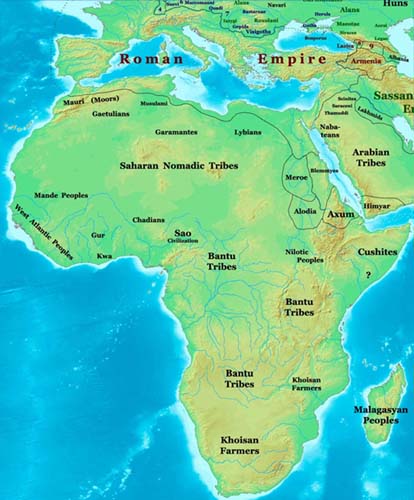

Below you find enlargements of map sections – do click on these and enjoy the view!

© Albi - Face Music 2007

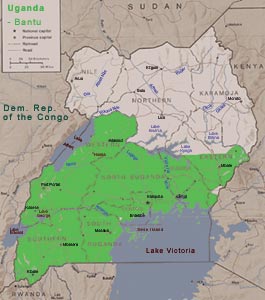

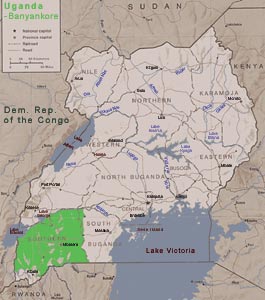

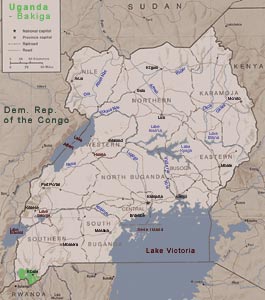

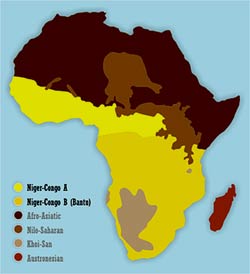

- The Bantu people

Bantu migrations |

Niger-Congo language |

For enlargements of map sections – do click! |

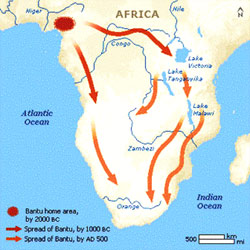

Movements by small groups from the Great Lakes region to the southeast were more rapid, with initial settlements widely dispersed near the coast and near rivers, due to comparatively harsh farming conditions in areas further away from water. Pioneering groups had reached modern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa along the coast by 300 A.D., and the modern Northern Province (formerly called the Transvaal) by 500 A.D. It is not clear when exactly the Bantu had moved into the savannahs to the south, in what are now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, and Zambia. Such processes of state formation occurred with increasing frequency from the 16th century onward. They were probably due to denser population, which led to more specialized divisions of labour, including military power, while making emigration more difficult, further due to increased trade among African communities and with European and Arab traders and the Coast people (Swahili) along the coasts (Indian Ocean), with technological developments in economic activity, and new techniques in the politicalspiritual ritualization of royalty as the source of national strength and health.

The Bantu expansion was a millenia long series of physical migrations, a diffusion of language and knowledge out into and in from neighbouring populations, and a creation of new society groups involving inter-marriage among communities and small groups moving to communities and small groups moving to new areas. Bantu speakers developed novel methods of agriculture and metalworking, which allowed people to colonize new areas with widely varying ecologies in greater densities than huntergatherers, the homeland people (original habitants of these regions). Meanwhile in eastern and southern Africa, Bantu speakers adopted livestock husbandry from other peoples they encountered, and in turn passed this form of living on to hunter-gatherers (San people), so that herding reached the far south several centuries before Bantu speaking migrants did. The linguistic and genetic evidence of all this supports the theory that the Bantu expansion was one of the most significant human migrations and cultural transformations within the past few thousand years in Africa.

Several successive waves of migrations over the following millennia followed on the tracks of the first. They were neither planned nor instantaneous, put took place gradually over hundreds and thousands of years, allowing plenty of time for Bantu culture to spread and be influenced by other cultures it came in contact with, either through assimilation or - rarer, it seems - conquest. Bantu culture most likely reached from the west, and possibly the south, some time between 200-1000 AD, having passed through what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). By 600 AD they had dispersed over enormous areas, covering what is now Tanzania and Mozambique on the East-African coast, south as far as the southern African coast and west into parts of Angola. The result of all this migration and integration was the development of more than five hundred Bantu-related languages sprinkled around this area of Africa.

The history of the Bantu migrations itself is some what confused, last but not least because the on-going process of fusion and mutual influence with neighbouring peoples meant that the tribes we know today did not actually emerge as distinct groups until about five hundred years ago at the earliest. And as the Bantu people met and absorbed other peoples, they also adopted some of the assimilated peoples' histories and traditions.

As cultivators, the Bantu sought out abundantly watered areas, often in the highlands, and they were the first to start large-scale forest clearance for cultivation, with the result that even today many Bantu areas suffer enormous losses of topsoil each year through erosion. Although the new-comers were frequently displaced, and though they sometimes fused with previous Bantu immigrants, Cushitic peoples (from whom some pastoral practices were adopted) or the hunters and gatherers they came in contact with, the essence of the Bantu identity remained the same, namely the reliance on agriculture, and hence a relatively settled way of life. Other Bantu cultural elements that have survived, and not just in Kenya, are cosmological beliefs, such as the belief in a single creator god, and, further, the belief in the survival of ancestors as spirits or intermediaries between the living and god.

The Gusii, Kuria and Luhya of Lake Victoria are the descendants of possibly the earliest Bantu groups to have arrived and are believed to have introduced iron smelting and the use of iron tools to the region. Although it is obvious that the Bantu must have moved north to populate the areas they cover today in Uganda and Kenya, the oral legends of the central highlands Bantu invariably point to the north - usually the Nyambene Hills which lie north of Mount Kenya - as their place of origin (ie. some five hundred years ago). From there, as their oral histories say, the ancestors of the present-day Kikuyu, Meru, Embu, Chuka and Kamba, and possibly others as well, migrated south into the foothills of Mount Kenya itself, where they eventually dispersed to their present locations. This would indicate that once in Kenya, the Bantu headed much further north than their present territories, and were pushed back by either the Nilotics or Cushites. This theory is backed-up by other oral histories which state that the central highlands Bantu came not from the north or west, but rather from the Indian Ocean coast to the east. The coastal Bantu themselves - the 'nine tribes' of the Mijikenda, together with the Pokomo - are unanimous in that they came from a semi-mythical place called Shungwaya in the north, which is likely to have been in what is now Somalia.

- The Bantu society

It seems that a long time ago many Bantu societies were organised along matrilineal lines and were governed by women; a whole heap of oral legends testifies to this, and female founding ancestors - where they exist in tradition - are as venerated and respected as their male counterparts.

Being a settled culture, the Bantu were inherently at risk of attack from the mobile nomadic Nilotic and Cushitic cattle and camel herders such as the Masaai, Borana (Oromo) and Somali, and as a result many Bantu societies became characterised by their defensive nature. Bantu groups lived on open land (ideal territory for the herders), having preferred, for both economic (agricultural) and defensive reasons, to occupy the less accessible highland regions. Settlements were built with the greatest attention to defence and were also well concealed: Europeans found they could be walking only metres from a settlement without knowing of its existence. Some tribes, like the Kikuyu, became experts at adapting and adopting to new realities, and rarely resorted to conflict. Others, like the Chuka, developed an array of inventive defensive measures, ranging from ingenious traps to tree houses and fortifications. Almost all the Bantu groups also adopted a rigid system of age-sets (an idea possibly borrowed from the Hamitic or Cushitic peoples they came across), in which all people of similar age were initiated into an age-set, which together progressed through clearly defined phases of social responsibilities, functions and status, from initiation, through warriorhood, marriage and elderhood to death. The system ensured the cohesion of society, as well as enabling the development of the warrior system, by which all the young men of a given society would, shortly after initiation to adulthood and their age-set, take up the role of defending the entire society.

Nowadays, the Bantu's reliance on agriculture and latterly trade has meant that they are by far the richest people, at least in monetary terms. The downside is that their settlements are inevitably densely populated, a problem which has grown acute over the last few decades.

- Songs and Dances of Bantu Women

The music of women in Bantu tribes is quite often part of the fabric of expression, which tells us who they are, not individually, but as a group - not in challenge to their culture, but in harmony with and support of the dominant and dynamic patterns of their culture. The songs and dances can be understood fully only by a tribe member, but we can benefit from an approach that looks at the textual content, the style (which includes their approach to composing), and the function of the songs and dances.

There is a conflict of presenting and, no doubt, mis-representing the dances and songs that have been extracted from the Bantu cultures. The weight of this wrong is proof to the vital interconnectedness of music and ways of life and meanings in Bantu culture. This has been said of many African cultures. Some Bantu-language have an expression for this loss of value in such an extraction: "You can take a feather from a bird, but when you get home that will not make you fly." In this way, music reflects a deep belief in the power of music to keep their life and culture alive. The traditional songs in women's lives, which they accompany, give proof for this. Thus, what we can see of the music and dance is out of context, but nonetheless all of its elements and expressions are purely reflective and confirming of life as it is in the culture of its origin. Also, we would have myopic view of women in Bantu cultures if we did not examine the African musical sensibilities that are the broader attitude towards music within culture. "Like a ritual or a musical event, an African community, too, is basically an ordered way of being involved through time. Africans rely on music to build a context for community action and, analogously, many aspects of their community life reflect their musical sensibility". Conventional to Western understanding of music is the identification of a work or song as a production of a single composer. However, composership in the African music system is not usually known to be authored by a particular individual. Either all the music is truly collaborative (not the case) and/or it is not important that individuals are credited with its creation. Music is often understood as a product of divine as well as mundane natural rhythms that are interpreted by villagers collectively. Again, music does not form a separate entity (from dance and from the holistic and daily culture); it is a communal production. Women, especially, have the solidarity of the other women and do not need to take individual credit for the composition they have created. Also, much of the song material is retained from generation to generation. The security of the form and the song allow for some freedom within it. The structure is so well known that individual women, especially dominant in voice, will improvise above that and thus transform aspects of the fabric of that song. The women who live this music do not seek originality but harmony. Especially in the group work songs it is clear that knowing the song and how it helps one to go about one's work in the village is more important that who first sung the melody. African women derive power and strength from social structure. It seems clear that we often consider women who defy social standards to be most powerful. An African woman expresses in her music that she is empowered by her positions as fixed by her culture. The song or dances, in their lyrics and in their place within a woman's world, provide an affirmation of identities such as mother, tiller of the earth, grinder of meal, midwife, socializing teacher or elder, or spiritual guide. The songs can be explicit messages to the community or a particular part of the community. They can be functional, providing necessary rhythms for human activity. Also, they can be narrative of an ongoing event or of well-known individuals. The women are the guardians of the life circle, from birth, through productivity and to death and again to birth. Musical elements that reflect the importance of a song within the unity of village women include: call and response, reassurance of participation (common inconverstion, too), apart-playing. "Africans respect ritualized social arrangements to externalize and objectify their sense of relationship because if a relationship is to be meaningful to them, the recognition one person gives another must be visible outside their own private involvement."

- Work songs identify the women as the workers: the tillers of the earth, and grinders of the corn, maize etc. The song utilizes the rhythm of the hoes hitting the earth and also guides the synchronized movement on the field of all the women. Thus the song develops a unity of rhythm on the microscale: the synchronized swinging of the hoes makes the work easier; but also on the macroscale: the symbolism of their common effort. They sing to remind each other of the worth of their work, as if to say, "We do this for the life of our families." The song is functional and explicit in it's purpose.

- Birth attendants, or midwives, of a village explain the role of a group of women. Their role in the village was mostly respected and a source of pride for them. The song, sung in the mother tongue of the region, is simple because its text - a "jingle" about a successful birth due to the presence of the midwife - is most important and it is sung with an accompanying dance. The song itself varies in melody.

- Lullabies - The syllables (or vocables) are soothing and repetitive. There is some word painting in that the lull and the sleep lyrics fall and lilt in the vocal line. We do hear the "rhythms of sleep", though perhaps for lack of cultural similitude the song sounds less subdued than we are accustumed to hear in a lullaby. A part of the text says, "Don't you dance on your feet, they must be lulled and feel the rhythms of sleep." The child is dependent on the mother (on whose back she rests) for mobility. In the culture of this song children are not allowed to cry if they can possible help it. This song seems to be especially insistent for that reason. The lullaby is functional and expressive of the woman as mother-socializer and caretaker.

- Morality story, to be told to a group of young girls. Old women grandmothers are also socializing agents. The grandmothers specifically have the duty to teach the girls lessons on hard or embarassing topics. They say that their mothers are too shy to preach to their own daughters in this way. The woman, especially as an elder, is the holder of the license to teach ethics to the young. Even in modern times, the primary female schoolteachers, and choir leaders in church, compose music and song to teach moral ideas to children. Hymns are set by women so that they can be sung in the home by the family, and school children learn songs that teach them to have gratitude for their elders.

- Life cycle - Women are major participants in the ceremonies of all the stages in traditional everyday life. When a new child is born, the women rejoice the occasion robustly. The child is the child of all the village women, not just his or her mother's. The choral texture of the example song is reflective of this sentiment.

On the occasion of initiation ceremonies of girls, old women beat drums, and the initiates, in Vinda culture, move through the village in a snake-like formation to express their belonging to this stage of life.

- Wedding celebration is marked by uproarious group singing as the women congratulate their age mates whom they will 'lose' to the husband's family, but who will now become a true and useful member of the community.

- Dirge songs - Even at the occasion of death, a woman is given the sacred right to sing the dirge. This is a Bantu cultural requirement of women for several days after a death in the family.

- The Baganda people

The Baganda passes through the stages of omwana (child), omuvubuka (youth), and omusajja or omukazi (man or woman). After death one becomes an omuzima (spirit), and the Baganda also believe in rebirth (reincarnation). After birth, the umbilical cord is retained for later use in a ceremony called Kwalula Abaana. During this ceremony the child gathers with other members of the father's clan to receive his/her name. Boys and girls are expected to conform in their behaviour to what the Baganda refer to as mpisa (manners). This includes being obedient to adults, greeting visitors properly, and sitting correctly (for girls). Sexual education for females is more systematic than it is for males. The father's sister (Ssenga) is the most significant moral authority for girls. Grandmothers instruct girls soon after their menstruation, during a period of seclusion, about sexual matters and future domestic responsibilities. Marriage and the birth of children are prerequisites for adult status. Women typically wear a busuuti. This is a floor-length, brightly coloured cloth dress with a square neckline and short, puffed sleeves. The garment is fastened with a sash placed just below the waist over the hips, and by two buttons on the left side of the neckline. Traditionally, the busuuti was strapless and made from bark-cloth. The busuuti is worn on all festive and ceremonial occasions. The indigenous dress of the Baganda men is a kanzu, a long, white cotton robe. On special occasions, it is worn over trousers with a Western-style suit jacket over it.

|

|

| Busuuti – children rests on the mothers back for mobility |

Kanzu – with a Western-style suit jacket |

The bark from a species of fig trees called mutuba is soaked in water, then beaten with a wooden mallet. This yields a soft material that is decorated with paint and then cut into strips of various sizes. Larger strips traditionally were used for partitions in homes. Smaller pieces were decorated with black dye and worn as clothing by women. They have been replaced by the cotton cloth Busuuti. Bark-cloth is found today as decorative placemats, coasters, and design on cards of various sorts.

The staple food of the Baganda is matooke (a tropical fruit of the banana family). It is steamed or boiled and commonly served with groundnut (peanut) sauce or meat soup. Furthermore, they live on eggs, fish, beans, groundnuts, beef, chicken, and goats as well as termites and grasshoppers according to the season. Common vegetables are cabbage, beans, mushrooms, carrots, cassava, sweet potatoes, onions, and various types of greens. Fruits include sweet bananas, pineapples, passion fruit, and papaya. Drinks made from bananas (mwenge), pineapples (munanansi), and maize (musoli). Baganda have cutlery, but most prefer to eat with their hands, especially at home. Their homes are usually made of wattle and daub (woven rods and twigs plastered with clay and mud). Generally, they have thatched or corrugated iron roofs. More affluent farmers live in homes constructed of cement, with tile roofs. Cooking is commonly done in a separate cooking house over an open wood fire. The traditional term for marriage was jangu enfumbire (come, cook for me). After the wedding, a new household is established, usually in the village of the husband. The husband and father was supreme. Children and women knelt in front of the husband in deference to his authority, and he was served his food first. Basketry is still a widespread art. These mats are colourful and intricately designed. Most Baganda are peasant farmers who live in rural villages. Rich red clay on hillsides, a moderate temperature, and plentiful rainfall combine to provide a good environment for the year-round availability of plantain, the staple crop, as well as the seasonal production of coffee, cotton, and tea as cash crops.

Traditional Dances - Every tribe in Uganda has at least traditional dances. For example "Baakisiimba, Nankasa, Muwogola" is a traditional dance that originated in the palace of the Buganda Kingdom. The Kabaka's Palace was a special place where royal dancers and drummers regularly performed. Dancing is frequently practised by all, beginning already in early childhood.

Riddles, myths and legends tell about the origin and history of the Baganda as well as the work of the real world. The most significant legend involves Kintu, the first Kabaka (king). He is believed to have married a woman called Nambi. Walumbe (Death) brings illness and death to children and then adults. Up to the present day, Death has lived upon the earth with no one knowing when or whom he will strike.

The Buganda believed in superhuman spirits. Balubaale were men who carried over into death. Mizimu were the ghosts of dead people. They believed that the soul still exists. The supreme power was the Creator, Katonda.

Some other Balubaale (about 37) had specific functions; there were the god of the sky, god of the rainbow, god of the lake, etc. They built for them all special shrines or temples. Temples were served by a medium or a priest who had powers over the temple. They also believed in spiritual forces, particularly the action of witches, who were thought to cause illness and other misfortune. People often wore amulets (charms) to ward off their evil powers. The most significant spirits were the Muzimu or ancestors who visited the living in their dreams and sometimes warned of impeding dangers. The Balubaale cult no longer exists. The belief in ancestors and the power of witches, however, is still quite common.

Each of the clans had a totem, which may not be eaten by a clan member, including: grasshoppers (nsenere), lungfish and one variety of beans. Ritual food: Food which was associated with feasts and celebration: Matooke (cook banana), sesame, mushrooms, chicken and some fish have played an important role in the celebrations of the Kiganda. Presents and gifts in the form of dowry were typical for weddings, also the ceremony for naming a child, especially on the occasion of the birth of twins.

Baganda is plural, while Muganda is singular, and they are often referred to simply by the rootsword and adjective, ganda. This region was never conquered in the colonial aera. The powerful King Mutesa (kabaka) agreed to a British policy of giving Buganda protectorate status. The traditional Ganda economy relied on crop cultivation. Cattlers played a minor role. Bananas were the most important staple food. Women did most of the agricultural work, while men often engaged in commerce and politics (and in precolonial times, warfare - warriors).

Ganda's social organization emphasized descent through males. Four or five generations related through male forebears constituted a clan. Clan leaders regulated marriage, which was always between two different lineages, forming important social and political alliances. They also helped to cultivate land, arrange ceremonies and rituals of remembrances for the ancestors. The Baganda were polygamous. A man could marry five wives or more. They feared death very much. They arranged great ceremonials. They did not believe that men would reach paradise after death. Death was a natural consequence, attributed to wizards, sorcerers and supernatural spirits. Ganda villages, sometimes as large as forty or fifty homes, were generally located on hillsides. Early Ganda villages surrounded the home of a chief or headman, which provided a common meeting ground for members of the village. The chief collected tribute from his subjects, provided tribute to the kabaka (king), distributed resources among his subjects, maintained order, and reinforced social solidarity through his decision-making skills. Late nineteenth-century Ganda villages became more dispersed as the role of the chiefs diminished in response to political turmoil, population migration, and occasional popular revolts.

Most lineages maintained links to a home territory (butaka) within a larger clan territory, but lineage members did not necessarily live on butaka land. Men from one lineage often formed the core of a village; their wives, children, and in-laws joined the village. People were free to leave if they became disillusioned with the local leader to take up residence with other relatives or in-laws, and they often did so. The family in Buganda is often described as a microcosm of the kingdom. The father is revered and obeyed as head of the family. His decisions are generally unquestioned. A man's social status is determined by those with whom he establishes patron-client-relationships, and one of the best means of securing this relationship is through one's children. Baganda children, some as young as three years old, are sent to live in the homes of their social superiors, both to cement ties of loyalty among parents and to provide avenues for social mobility for their children. Ganda culture tolerates social diversity more easily than many other African societies. Even before the arrival of Europeans, many Ganda villages included residents from outside Buganda. Some had arrived in the region as slaves, but by the early twentieth century, many non-Baganda migrant workers stayed in Buganda to farm.

The Buganda Kingdom

The twentieth-century influence of the Baganda in Uganda has reflected the impact of 18th and 19th century developments. A series of kabakas (kings) amassed military and political power by killing their rivals. Ganda norms also prevented the establishment of a royal clan by assigning the children of the kabaka to the clan of their mother. At the same time, this practice allowed the kabaka to marry into any clan in the society.

Traditionally, the kabaka ruled over a hierarchy of chiefs who collected taxes in the form of food and livestock. The kabaka made direct political appointment of all chiefs so as to maintain control over their loyalty to him. Many rituals surrounded the person of the king. Commoners had to lie face down on the ground in his presence. Today, the kabaka has only ritual functions and no political power.

One of the most powerful advisers of the kabaka appointed was the katikiro, who was in charge of the kingdom's administrative and judicial systems effectively serving as both prime minister and chief justice. The katikiro and other powerful ministers formed an inner circle of advisers who could summon lower-level chiefs and other appointed advisers to confer on policy matters. By the end of the nineteenth century, the kabaka had replaced many clan heads with appointed officials and claimed the title "head of all the clans."

Kabaka Mutesa started to claim territory as far west as Lake Albert, and he considered the agreement with Britain to be an alliance between equals. Baganda armies went on to help establish colonial rule in other areas, and Baganda agents served as tax collectors throughout the protectorate. The power of the kabaka impressed British officials, but political leaders in neighbouring Bunyoro were not receptive to British officials who arrived with Baganda escorts. Buganda became the centrepiece of the new protectorate, and many Baganda were able to take advantage of opportunities provided by schools and businesses in their area. Baganda civil servants also helped administer other ethnic groups, and Uganda's early history was written from the perspective of the Baganda and the colonial officials who became accustomed to dealing with them.

Trading centres in Buganda became important towns in the protectorate, and the Baganda took advantage of the opportunities provided by European commerce and education. At the time of independence in 1962, Buganda had achieved the highest standard of living and the highest literacy rate in the country.

History of Buganda

The early history of Buganda has been passed down from one generation to the next one as oral history. Unfortunately, as with many cases of oral history, the stories have taken on several different versions depending on the source. There are different versions of history detailing how the kingdom of Buganda was established as given below.

The Coming of Kintu

Prior to the establishment of Kintu's dynasty, the people who lived in the area that came to be known as Baganda had not been united into a single political entity. The people were organized into groups that had a common ancestry and constituted the most important unit in Buganda's culture - the clan. Despite a common language and culture, the clans were loosely autonomous. The clan leaders (abataka) ruled over their respective clans. There was no caste system and, all clans were equal. This did not preclude the fact that from time to time, the leader of one clan might be militarily stronger than the others. In such a case, the leader could establish hegemony over the other clans for a time.

According to the most widely accepted version of history, Bemba was the leader at the time of Kintu's arrival. Kintu came into Buganda as a conquering hero. It seems that at that time, Buganda was very sparsely populated. He is reputed to have brought 13 clans (bannansangwawo) with him and been able to establish himself as king. Another factor may have been that Bemba was a harsh and ruthless ruler. His subjects were already primed to rebel against him, and, indeed, some prominent clan leaders joined Kintu's invading force. Key among those was Mukiibi, head of the Lugave clan, who was assigned command of the invading force. Another interesting side is that Buganda was the name of the house in which Bemba used to live. This house was located at Naggalabi, Buddo. When Bemba was defeated in battle, Kintu slept in Bemba's house as a sign of his victory. Thus Kintu became the 'ruler' of Bemba's house. This name eventually came to mean all the territory that Kintu ruled. To this day, when a new king of Buganda is crowned, the ceremony takes place at Naggalabi, to recall Kintu's victory over Bemba. After the battle to oust Bemba, there was a general conclave of the clans and clan elders that was held at Magonga in Busujju country, on a hill called Nnono. This meeting was of great historic significance, for it was at this meeting that Buganda's form of governance, and the relationship between the clans and the King was formally agreed upon. Although it was unwritten, this constituted an understanding between the clans that has been followed since then. In essence, it set down Buganda's Constitution. After the meeting, Bukulu returned to the Ssese Islands. On completing his victory, Kintu established his palace at Nnono. It is here that he appointed his first government and awarded chieftaincies to his prominent followers. For this reason, Nnono is one of the most important cultural and historical sites in Buganda. It is also for this reason that when the people of Buganda talk about issues of deep cultural significance, they refer to them as being of or from Nnono (ebyennono). In addition to military conquest, Kintu cleverly allied himself with the leaders of the original clans. Kintu was the first king in Buganda to share his authority with the other clan leaders. This may also have played a key role in getting him accepted as the king of Buganda. In organizing the kingdom, Kintu conceded to the clan leaders authority over their respective clans in matters of culture. Kintu then became mediator between the clans in case of disputes, thus cementing his role as Ssaabataka, head of all the clans.

- Other versions of Kintu's Story:

Version 1:

Prior to Kintu's time, Buganda used to be called Muwaawa. The head of the Ffumbe clan was called Buganda Ntege Walusimbi, and it was he who had leadership over all other clans. Walusimbi had several children including Makubuya, Kisitu, Wasswa Winyi, and Kato Kintu. When Walusimbi died, his son Makubuya replaced him as ruler. On his death, Makubuya in turn was replaced by his brother Kisitu as ruler. During Kisitu's reign, a renegade prince called Bemba came from the area of Kiziba (now in northern Tanzania) and established camp at Naggalabi, Buddo. From there he sought to fight Kisitu and replace him as ruler of Muwaawa. Bemba had a reputation of being cruel and ruthless. Apparently, Kisitu was easily intimidated and in his fear, he vowed to give his chair Ssemagulu to whoever would succeed in killing Bemba. (This Ssemagulu was the symbol of authority.)

On hearing his brother's vow, Kintu gathered some followers from among his brother and some of the various clans and attacked Bemba. Bemba was defeated in the ensuing battle, and he was beheaded by one Nfudu of the Lugave clan. Nfudu quickly took Bemba's head to Kintu, who in turn took it to Kisitu. On seeing Bemba's head, Kisitu abdicated his throne in favour of Kintu with the words "Kingship is earned in battle". Despite his abdication, Kisitu wanted to retain leadership of the Ffumbe clan, and so he told Kintu to start his own clan. He also told Kintu that the kingdom should be renamed Buganda in memory of their common ancestor Buganda Ntege Walusimbi. Hence, the royal clan was separated from the Ffumbe clan. Kintu established a new system of governace in alliance with the other clan leaders, as we already saw earlier.

Version 2:

Other stories suggest that Kintu was not indigenous to Buganda. Some assert that he came from the East, near Mt. Elgon. Kato Kintu came with his elder brother Rukidi Isingoma Mpuga. Rukidi conquered the lands of Bunyoro where he established himself as king. According to this version, the area that formed the core of Buganda was in fact a remote outpost of the kingdom of Bunyoro. Rukidi sent his brother Kato to govern this outpost, but on reaching the area, the younger brother essentially broke away from Bunyoro and established his own kingdom that came to be known as Buganda. Another version gives essentially the same story but instead suggests that Rukidi and Kato came from the northern area around Madi (South Sudan). They landed at a port called Podi, which was in the country of Bunyoro. From there Kintu reached Kibiro with many of his followers. They were: Bukulu and his wife Wada; Kyaggwe and his wife Ndimuwala; Kyaddondo and his wife Nansangwawo; Bulemezi and his wife Kweba; Mazinga and his wife Mbuubi.

Some suggest that Rukidi's brother Kato was called Kimera rather than Kintu. According to this school of thought, Kintu was merely a mythical figure and Kimera is the one who established the royal dynasty of Buganda. The Baganda people strenuously resist this theory, and instead assert that Kimera was a grandson of Kintu. Kimera is counted as the third king in the dynasty, rather than its founder. More will be said about Kimera later.

Version 3:

Another version of Kintu's story suggests that he was born in Ssese or Bukasa Island. According to this version, Kintu's father was Kagona, and his mother was Namukana. Bemba was ruler on the Buganda mainland but he was very unpopular. He alienated the clan leaders in his efforts to establish his authority over them. Mukiibi, head of the Lugave clan, was one such leader who rebelled against Bemba. Bemba was not amused by Mukiibi's rebellion, and he attacked him. Mukiibi fled to Ssese to save his life. There, he allied himself with Kintu and they raised an army that attacked Bemba and deposed him from the throne.

It is notable that the kings of Buganda never established direct rule over the islands of Ssese, like they did with other areas under their dominion, although it was well accepted that the islands formed part of the territory of Buganda. Indeed, Ssese was only made a county and given a county chief under the 1900 agreement. The Ssese islands were referred to as the islands of the gods. All the original clans, as well as those that came with Kintu, have important shrines in Ssese. For this reason, some have suggested that wherever Kintu came from, he must have come through Ssese at some point to get to Buganda. Ssese was thus the springboard from which Buganda was created, and consequently was never subjected to direct rule in recognition of this pivotal role.

Version 4:

In his book "Ssekabaka Kintu ne Bassekabaka ba Buganda Abaamusooka" (in Luganda, a Bantu dialect, published by Crane Publishers Ltd.) Chelirenso E. S. Keebungero presents a cogent case for the argument that Kintu was indigenous to Buganda rather than an invading all conquering hero. The book reports of extensive research among clan elders asserting that Kintu was in fact born in Buganda. Kintu is said to have been the son of King Buganda (after whom the kingdom took its name), and that King Buganda did indeed exist is fairly well established and his shrine is known to be at Lunnyo, near Entebbe in Busiro. According to this version, King Buganda was deposed by his brother Bemba. As stated elsewhere, Bemba was a ruthless and unpopular ruler. So the clan elders concocted a secret plot to take the late king's young sons out of the country. They were sent to the Masaaba mountains to the east (now Mt. Elgon) and there looked after by royal attendants until they had matured enough to lead an army into battle. When the time was judged to be right, the elders sent messengers to Masaaba who returned with Kintu the prince. They then joined Kintu in the successful battle to oust Bemba.

Kintu, the Person

The legend of Kintu is told by the Baganda as the story of the creation. According to this legend, Kintu was the first person on Earth. Unfortunately, many writers of the history of Buganda have confused the two people called Kintu, i.e. Kintu, the first king of Buganda, and Kintu, the alleged first man on Earth. This confusion has led some to conclude that there never was a king called Kintu, and that Kintu is merely a legend. What Baganda scholars assert, however, is that Kintu was indeed a legend about the creation of man. Creation stories abound in all cultures, and that there should be a creation story among the Baganda is not surprising. Thus the Baganda regarded the Kintu in this legend as the father of all people. It appears that when Kato established himself as king, he gave himself the name Kintu, a name that he knew the Baganda associated with the father of all people. Thus Kintu was in effect trying to establish his legitimacy as ruler of the Baganda people by associating himself with the legendary first person in Buganda. It is for this reason that he also named his principal wife Nambi. With that in mind, let us now detail the legend of Kintu, the first person on Earth.

Kintu, the Legend

Long long ago, Kintu was the only person on Earth. He lived alone with his cow, which he tended lovingly. Ggulu, the creator of all things, lived up in heaven with his many children and other property. From time to time, Ggulu's children would come down to earth to play. On one such occasion, Ggulu's daughter Nambi and some of her brothers encountered Kintu who was with his cow in Buganda. Nambi was very fascinated by Kintu, and she felt pity for him because he was living alone. She resolved to marry him and stay with him despite the opposition from her brothers. But because of her brothers' pleading, she decided to return to heaven with Kintu and ask for her father's permission for the union.

Ggulu was not pleased that his daughter wanted to get married to a human being and live with him on Earth. But Nambi pleaded with her father until she persuaded him to bless the union. After Ggulu had decided to allow the marriage to proceed, he advised Kintu and Nambi to leave heaven secretly. He advised them to pack lightly, and that on no condition were they to return to heaven even if they forgot anything. This admonition was so that Walumbe, one of Nambi's brothers, should not find out about the marriage until they had left, otherwise he would insist on going with them and bring them misery (Walumbe means that which causes sickness and death). Kintu was very pleased to have been given a wife, and together they followed Ggulu's instructions. Among the few things that Nambi packed was her chicken. They set out for earth early the next morning. But while they were descending, Nambi remembered that she had forgotten to bring the millet to feed her chicken on. "I have left my chickens' millet on the porch, let me return and fetch it," she begged Kintu. But Kintu refused and said, "Don't go back. If you do, you will meet Walumbe and he will surely insist on coming with you." Nambi, however, did not listen to her husband, and leaving him on the way she returned to fetch the millet. When she reached the house, she took the millet from the porch, but on her way back she suddenly met Walumbe who asked: "My sister, where are you going so early in the morning?" Nambi did not know what to say. Filled with curiosity, Walumbe insisted on going with her. Therefore Kintu and Nambi were forced to go to Earth together with Walumbe. It did not take long for Kintu and Nambi to get children. One day, Walumbe went to Kintu's home and asked his brother-in-law to give him a child to help him with the chores in his (Walumbe's) house. But remembering Ggulu's warning, Kintu would not hear of it. Walumbe became very angry with Kintu for refusing him the simple favour he had asked. That very night, he went and killed Kintu's son. Naturally, this caused a deep rift between them. Kintu went back to heaven to report Walumbe's actions to Ggulu. Ggulu rebuked Kintu, reminding him of the original warning he had disregarded. Kintu blamed Nambi for returning to get the millet. Ggulu then sent another of his sons, Kayikuuzi, to go back to earth with Kintu and try to persuade Walumbe to return to heaven or, if necessary, return him by force. On reaching Earth, Kayikuuzi tried to persuade Walumbe to go back to heaven but Walumbe would not hear of it. "I like it here on Earth and I am not coming back with you", he said. Kayikuuzi decided to capture Walumbe by force, and a great fight broke out between them. But as Walumbe was about to be overpowered, he escaped and disappeared into the ground. Kayikuuzi went after him, digging huge holes in the ground to try to find his brother. When Kayikuuzi got to where he was hiding, Walumbe run back out to the earth. Further struggle between the brothers ensued but once again Walumbe escaped into the ground. The famous caves that are found today at Ttanda in Ssingo are said to be the ones that were dug by Kayikuuzi in the fight with his brother Walumbe. (Kayikuuzi means he who digs holes). The struggle went on for several days and by now, Kayikuuzi was close to exhaustion. So he went and talked to Kintu and Nambi as follows: "I am going back into the ground one more time to get Walumbe. You and your children must stay indoors. You must strictly enjoin your children not to make a sound if they see Walumbe. I know he is also getting tired so when he comes out of the ground, I will come upon him secretly and grab him." Kintu and Nambi went into their house, but some of the kids did not go in. Kayikuuzi once again went underground to find Walumbe. After a struggle, Walumbe came back out to the surface with Kayikuuzi in pursuit. Kintu's children who were outside at the time saw Walumbe coming and sreamed in terror. On hearing the screams, Walumbe went underground once again. Kayikuuzi was furious with Kintu and Nambi for not having followed his instructions. He told them that if they did not care to do the simple thing he had asked of them, he was also giving up the fight. Kintu in his embarrassment had nothing more to say. So he told Kayikuuzi "You return to heaven. If Walumbe wants to kill my children, let him do so, I will keep having more. The more he kills, the more I will get and he will never be able to kill all my children". Ttanda, where the fight between Walumbe and Kayikuuzi allegedly took place, is figuratively referred to as the place of death (i.e. Walumbe's place).

So that is the legend of creation, and how sickness and death started. Nonetheless, Kintu's descendants will always remain as Kintu said in his last words to Kayikuuzi. Hence the Kiganda saying "Abaana ba Kintu tebalifa kuggwaawo". Which means that Kintu's children (i.e. the Baganda) will never be wiped off the face of the earth.

What about Kimera?

Most historians agree that there is a close relationship between the royal families of Buganda and Bunyoro. What is debatable, however, is the nature of the relationship, and the point of time when the two separated. We will now address the issue of who Kimera was according to the oral tradition of the Baganda. When Kintu died, his officials did not want to make this public knowledge, fearing that this might cause instability in the kingdom. So Kintu was buried secretely at Nnono, and the officials put out the word that the king had disappeared. After some time, the officials chose Ccwa, one of Kintu's sons, to become king in his father's place. Ccwa had only one son called Kalemeera. Kalemeera was only a young boy by the time his father ascended the throne. As he became older, Kalemeera began to understand the significance of the story that his grandfather Kintu had disappeared. He became apprehensive that his father Ccwa might also disappear in the same way. Thus Kalemeera began to follow his father around everywhere he went, fearful of letting him out of sight. Eventually, Ccwa became exasperated with his son's behaviour and he concocted a plan that would force Kalemeera to leave his father's side.

The scheme that was concocted involved Walusimbi the Katikkiro (Prime Minister) falsely accusing Kalemeera of having had an illicit affair with his wife. When the case was brought before Ccwa, the king ruled against his son, and he fined him heavily. Kalemeera was forced to go to Bunyoro to seek the help of king Winyi in paying off the fine. (According to this version of history, Winyi was the son of Rukidi Mpuga Isingoma, founder of the Bunyoro dynasty. But since Rukidi was Kintu's brother and Kintu was the father of Ccwa, it follows that Winyi was Kalemeera's uncle and he was in a position to help him out at this hour of need). Bunyoro at that time was the only source of iron implements in the whole region and Kalemeera's plan was to import some of these into Buganda and use the profits to help pay off the fine.

The story continues that while in Bunyoro, Kalemeera had an affair with Wannyana, one of Winyi's wives. When it became evident that Wannyana had become pregnant as a result, Kalemeera decided to quickly return to Buganda to escape Winyi's wrath. Unfortunately for him, Kalemeera took ill on the way home and he died. His attendants took his skull and buried.

Folktales

Folktales define community; reflect the history, traditional values and accumulated wisdom. Every culture has its own collection of ancient and traditional stories that have been orally transmitted from generation to generation.

Baganda women told these stories to the children in the evening after work and before they had to go to bed around a fire. In some of the stories, general animals, birds and plants have human characteristics (souls), by means of which they talk and develop relationships with humans. They have a supernatural element which allows them to perform tasks only in folktales.

Stories have always been very significant to the tradition and the culture of Buganda. The young generation has been taught about the past of their kingdom, they have learnt about their ancestors, cultural taboos, history, values of life, etc.

Traditionally, the stories or legends were a main source of education in the African life style, that involved participation, which was oral and it was the way to teach the young ones to used and to know almost everything about their culture, people and historical background.

Traditional storytellers (Bards and Griots)

The ancient oral tradition of storytelling by the bards or griots still exists. Each people has its very own term for this highly refined and deeply spiritual discipline, as these artists are masters in reciting epics and many other stories. The power of these storytellers is breathtaking, and they guide through the experiences of life of most people. It is a privilege to have seen such still unbroken living tradition, which has survived for thousands of years and has nothing in common with the modern revival of storytelling (songwriters). Their roles are often as spiritual teachers for whom the stories and music become a medium as well as historians and traditionbearers. People today are rediscovering this oral tradition with all its wisdom, with the pleasure of telling stories about the people's actual life and roots (songwriters).

The traditional African storytelling was performed within the community. In African societies everyone participates in formal and informal storytelling as an interactive oral performance — such a form of participation is an essential part of traditional African communal life and constitutes the basic training in a particular culture’s oral arts and skills. These are performed in an interactive "call-and-response"; and everywhere in Africa it is the soloist who "raises the story (the song line)", and the community brings the chorus responding, or "will agree during the song."

There are stories that have been drawn on the walls of caves and which were depicted in rock paintings in early times (e.g. San people in South Africa). Painted stories were used to explain the power of nature that normal humans did not understand und had to be translated into the form of stories. There are also stories that tell about the creators, gods and heroes; stories that reminded people of behaviour that was good and would be helpful for others, of the taboos, as well as of behaviour that was evil and not to be accepted. These stories have a basic theme or message that has been passed down through generations.

There are two kinds of storytellers in Africa. The best known are griots, who come from West Africa. Griots are historian tellers, praise-singers and musical entertainers who know the entire history of families, the struggles of them and their ancestors; they know who married whom, when and where, and they know all the children born. They also tell the stories of entire villages – tales of feast and famines, tales of prosperity and destruction, tales of good times and bad times. They perform at great annual celebrations where there are large gatherings of people to celebrate this special occasion or to perform ceremonies. In West Africa anybody who wanted to be a griot had to be born into a family of griots. The knowledge is passed down from parents to children. In some tribes, such as the Malinke from Mali, the griots are part of a caste, a separate social group. Members cannot marry outside their caste.

The second kind of African storytellers performs in everyday places, such as the marketplace, at festivals, or at family parties. These storytellers sometime wear hats, or they display story nets on which such things as a bone, a skull, or a rattle are hung. Each item represents a story that can be told.

African storytelling and orature are highly skilled performance acts in art. These living traditions continue to survive and to adapt to the challenges of modernization characteristic for today's Africa, and they have fused, in uniquely African ways, in newer forms, and with all these influences they enrich the global human experience and its creative expressions around the world. In modern times such epic forms and theatre groups are even used when lecturing children; thereby the children are stimulated to participate and the stories become experiences to be made by all of them.

- The Bagwere people

In the older times, parents have arranged marriages for their children. However, later, it became customary for a boy to look for a girl. Upon consent, the girl would introduce the boy to her parents. On being introduced, the groom would offer something as a gift to the bride's parents. The bridewealth had to be paid later on. This practice was known as okutona. The process that followed involved the boy inviting the girl’s parents to come to his family home in order to assess the bridewealth. The bride and the groom getting married would stand under a tree and take a bath in the same water refined with appropriate herbs. Then the community started singing, and they would prepare to come to the courtyard.

Whenever a woman was pregnant, she was not supposed to look at the nest of a bird called Nansungi. It was believed that if the woman looked at the nest, she would miscarry. After giving birth, the woman was not supposed to leave the home. She was given banana leaves to sleep on. Custom demanded that she was not allowed to eat food from her husband’s clans until her days of confinement were over. During this time, she could eat food provided by her neighbours or in her parents’ home. The name was given by the grandmother or aunt of the child. Some names had a special meaning but some did not.

If one died, people would weep and wail loudly. If some one did not cry or only cried lightly, he could be easily suspected of having had a hand in the death of this person. If the deceased man was an old man, the people would move around singing and mourning and they would tour the immediate neighbourhood and on to the well, to take away the spirit of the dead. Normally, the body could not spend more than two days in the house before being buried. Corpses used to be buried with a needle or mweroko, a small stone used for grinding, to furnish the corpse with a means of defense against cannibals (body hunters). It was believed that if the body hunters called upon the corpse to come out of the grave, the corpse would reply that it was busy either sewing or grinding, whatever the case may be. Normally there were three days of mourning. This perdiod of mourning would be ended by a ritual ceremony called okunaba. Herbs would be pounded and mixed in water. This mixture was then sprinkled on everybody present and on to the doorway of the deceased’s house. Finally, a goat would be slaughtered and eaten. The night before okunaba, the bayiwa (nieces and nephews) would be given a chicken to slaughter and eat because of their significant role during the funeral rites. They would also remove whatever rubbish was scattered around and they were customarily paid for that act. The burial of a suicide case differed significantly from that of a normal death. There was no weeping, and no prayers were offered. A sheep was slaughtered to be eaten by the bayiwa alone, perhaps because of the unlucky task of cutting the rope which the bayiwa were used to perform. The tree on which the suicide person had hanged himself had to be uprooted and burnt. If the deceased had hanged himself in the house, the house was destroyed and burnt, however big or good it was. This happened because such a house was believed to be contaminated.

The Bagwere were mostly agriculturalists, and their main crops were millet, matooke, potatoes, sorghum (an old type of grain), and cassava. They have known a large sortiment of beans, peas, groundnuts and pumpkins. Now they also grow rice. They have also kept cows, goats, sheep and chicken. Their women were not supposed to eat mamba (lung of the fish), chicken, eggs and a particular kite-like bird called wansaka.

The traditional music of the Bagwere is called entongoli, like the five string lead instrument, that shows similarities to the most popular instrument in use in Western Africa, this is the kora. They use this lute or the akogo, the thumb piano, to accompany their songs. It is further known that they also play the namadu, the so-called set of seven drums. The clan Balangira uses special drums for particular functions. They dance during funerals, especially when the deceased was very old or very important; during wedding ceremonies in particularly before the ritual ceremony of okunaba (day before the actual wedding takes place); at occasions of merry festivities such as visits and beer parties; during a ritual dance called eyonga. If the woman gave birth to twins, she would go with some people to dance eyonga as one of the rituals of inviting the twins into the community.

- The Banyoro people

- Runyege / Entongoro dance -This is a ceremonial dance from Bunyoro and Toro (Batooro) Kingdom. It is also a courtship dance performed by the youth when it is time for them to choose partners for marriage. The dance was named after the rattles (ebinyege - binyege - entongoro) that are tied on boys'legs to produce percussion - like sound on rhythm. The sound produced by rattles is more exciting as it is well syncopated as the main beat is displaced but everything blending with the song and drum rhythms.

Once upon a time, there was a problem in the Kingdom when over 10 men wanted to marry the same beautiful and good-looking girl. What happens is that a very big ceremony is organized and all the male candidates have to come and dance. The girl had to choose the best male dancer. In this culture it is believed that the best dancers also show the best marriage life. It is also to see who is the strongest among the men as families in Africa do not want to give their beautiful girls to weak men, for when there is a period of drought or famine, one should have a husband who will really struggle to see that he looks for water and food. So in this dance the man who gets tired first, loses first and that who dances till the end wins the game. There was a problem when some girls wanted to get married to particular men and these were the men who got tired first - what a pity! The girls did not have a choice, as their parents decide for them whom to marry.

The western Lacustrine Bantu people includes the Banyoro, Batooro , and Banyankore: their complex kingdoms are believed to be the product of acculturation between two different ethnic groups, the Hima and the Bayira. The Hima are said to be the descendants of pastoralists who migrated into the region from the northeast. The Bayira are said to be descendants of agricultural populations that preceded the Hima as cultivators in the region. Bunyoro region lies in the plateau of western Uganda, constituting about 3 per cent of the population. Its nucleus is Masindi and Hima. The Batooro region evolved out of a breakaway-segment of Bunyoro that split off an unspecified time before the nineteenth century. The Batooro and Banyoro speak closely related languages, Rutooro and Runyoro (a Bantu language), and they share many other cultural traits. The Batooro live on Uganda's western border, south of Lake Albert and constitute about 3.2 per cent of the population. In pre-colonial times, they lived in a highly centralized kingdom like Buganda, which was stratified like the society of Baganda people.

Traditionally, a Munyoro (singular) had just one ibara (name) and one empaako (praise name) which were given to him / her shortly after birth. This name has always been a kinyoro name. Officially, the name is given by clan elders; but practically, the will of the parents is paramount in this decision. Like most African names, kinyoro names are actually words or phrases in the Runyoro language; and they have a meaning. This meaning is based upon the prevailing circumstances in the family or clan at the time of the child's birth. For example, the name Nyamayarwo (meat for Death) implies that the parents are prepared for the worst, because many of their children have already died. Names like Ndyanabo (I eat with evil people), Nyendwooha (who loves me no one), Nsekanabo (I laugh with the evil people), etc. portray the sentiments of parents very ill at ease with their neighbours. Following the introduction of Christianity, a new class of names was created. It was the Christian name, given upon baptism. Many Banyoro took on English names like Charles, Henry, George, etc. for their Christian names; while others took names from the Bible, like Matayo (Matthew), Yohana (John), Ndereya (Andrew), etc. It is to be noted that Islam is an important part of Bunyoro's religious heritage; so all Banyoro of Islamic belief will have an Islamic name, in addition to their kinyoro name. Names like Muhamadi (Muhamad / Mohamed), Isimairi (Ismael), Arajabu (Rajab), Bulaimu (Ibrahim), etc. are common. There are special names given to twins and the children following twins. These names are standard. When twin boys are born, the first one to be born is Isingoma, the other Kato. The female versions are Nyangoma and Nyakato, respectively. If a person is named Kaahwa, he / she comes after twins.

Unique to Banyoro and Batooro are praise names, empaako. These names are given at the same time when a child is given its regular, kinyoro name. They are special names used to show love and respect. Children call their parents by the empaako, not the regular name. The empaako is also the salutation when the Banyoro greet each other. Instead of the Western quot "Good morning, John"; the Banyoro substitute the empaako for John. There are eleven empaako names, shared by all Banyoro and Batooro. They are Abwooli, Adyeeri, Araali, Akiiki, Atwooki, Abbooki, Apuuli, Abbala, Acaali, Ateenyi and Amooti. The official empaako of the omukama (king) is always Amooti, regardless of what it used to be before he became the omukama. Another, very special, empaako reserved for the omukama alone is Okali. Contrary to the general rule that kinyoro names have a meaning, the empaako names do not have a kinyoro meaning because they are not, real, words in the Runyoro-Rutooro language. They are words (or corruptions of words) in the Luo language, the original language of the Babiito, who invaded and colonized Bunyoro from the North. The Banyoro and Batooro people have, however, assimilated these Luo names into their language, and even attempted to append some meaning to them. For example, Ateenyi is the great serpent of River Muziizi; Abwooli is the cat; Akiiki is the savior of nations; Acaali is lightning, etc.

Every Munyoro (singular from Banyoro) belongs to a clan. The clan is the collective group of people who are descendants from the same ancestor, and are, therefore, blood relatives. Long before the tradition of kingdoms, the Banyoro lived in clan groups. Areas of the land were named after the clan that lived there. For example, Buyaga was the area of the Bayaga clan, Buruli for the Baruli clan, Bugahya for the Bagahya clan, etc. The clan is very important to a Munyoro, man or woman. It is important that one is well aware of the clan relationships on both mother's and father's side of the family. This is crucial in order to avoid in-breeding. One cannot marry in one's own clan or in that of his / her mother. Marriage to one's cousins, no matter how far removed, is not acceptable. An exemption from this rule is claimed by the princes and princesses of the kingdom. In their effort to maintain their "blue blood lines", it is not unheard of for the royals of Bunyoro, Batooro and Buganda to marry very close to their own or their mothers' clans.

- The Batembuzi Dynasty

The first kings were of the Batembuzi dynasty. Batembuzi means harbingers or pioneers. The Batembuzi and their reign are not well documented, and they are surrounded by a lot of myths and oral legends. There is very little concurrence, among scholars, regarding the Batembuzi time period in history, even the names and successive order of individual kings. It is believed that their reign dates back to the time of Africa's bronze age.

- The Babiito Dynasty

Any attempt to pinpoint the dates of this, or any other dynasty before it, is pure conjecture; as there were no written records at the time. Modern-day-historians place the beginning of the Babiito dynasty at around the time of the invasion of Banyoro by the Luo from the North. The first Mubiito (singular) king was Isingoma Mpuga Rukidi I, whose reign is placed around the 14th century.

- The Bachwezi Dynasty

The Bachwezi dynasty was followed by the Babiito dynasty of the current omukama (king) of Bunyoro-Kitara. The Bachwezi are credited with the founding of the ancient empire of Kitara; which included areas of present-day central, western, and southern Uganda; northern Tanzania, western Kenya, and eastern Congo. Very little is documented about them. Their entire reign was shrouded in mystery, so much so that they were accorded the status of demi-gods and worshipped by various clans. Many traditional gods in Batooro, Bunyoro and Buganda have typical kichwezi (adjective) names like Ndahura, Mulindwa, Wamara, Kagoro, etc.

The Bachwezi dynasty must have been very short, as supported by only three names of kings documented by historians. The Bachwezi kings were Ndahura, Mulindwa and Wamara; in this order.

In addition to founding the empire of Kitara, the Bachwezi are further credited with the introduction of the unique, long-horned Ankole cattle, coffee growing, iron smelting, and the first semblance of organized and centralized government, under the king.

No one knows what happened to the Bachwezi. About their disappearance, there is no shortage of colorful legends. One legend claims that they migrated westward and disappeared into Lake Mwitanzige (Lake Albert). There is a small crater lake in preday Fortpotal that others they disapeared into.

Another legend has them disappearing into Lake Wamala, which bears the name of the last king of the dynasty. There is a popular belief among scholars that they simply got assimilated into the indigenous populace, and are, today, the tribal groups like the Bahima of Ankole and the Batutsi of Rwanda. The Bahima and Batutsi have the elegant tall build and light complexion of the Bachwezi, and they are traditionally herders of the long-horned Ankole cattle.

Bachwezi (Chwezi): According to oral tradition they were supposed to be demi-gods; even if they were born of men and women, they did not die. They are portrayed as standing with one leg in the world and the other one in the underwold. They ruled the Kitara empire after the Babiito Dynasty.

Today the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara is the remainder of a once powerful empire of Kitara. At the height of its glory, the empire included present-day Masindi, Hoima, Kibale, Kabarole and Kasese districts; also parts of present-day Western Kenya, Northern Tanzania and Eastern Congo. That Bunyoro-Kitara is only a skeleton of what it used to be is an absolute truth to which history can testify. One may ask how a mighty empire like Kitara, became the presently underpopulated and underdeveloped kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. This is the result of many years of orchestrated, intentional and malicious marginalization, dating back to the early colonial days.

The people of Bunyoro, under the reign of the mighty King Ccwa II Kabalega, resisted colonial domination. Kabalega, and his well-trained army of "abarusuura"; (soldiers), put his own life on the line by mounting a fierce, bloody resistance against the powers of colonialization. On April 9th, 1899, Kabalega was captured by the invading colonial forces and was sent into exile on the Seychelles Islands. With the capture of Kabalega, the Banyoro were left in a weakened military, social and economic state, from which they have never fully recovered. Colonial persecution of the Banyoro did not stop at Kabalega's ignominious capture and exile. Acts of systematic genocide continued to be carried out against the Banyoro, by the colonialists and other foreign invaders. Colonial efforts to reduce Bunyoro to a non-entity were numerous, and they continued over a long period of time. They included invasions where masses were massacred; depopulating large tracts of fertile land and setting them aside as game reserves; enforcing the growth of crops like tobacco and cotton at the expense of food crops; sanctioning looting and pilaging of villages by invading forces, importing killer diseases like syphilis that grew to epidemic proportions; and so on.

The omukama (king) of Bunyoro-Kitara Kingdom, however, was restituted by Statute No. 8 of 1993, enacted by the Parliament of Uganda, after the monarchy had been abolished for 27 years. Unlike the pre-1967-Omukama who was a titular head of the local government of Bunyoro, the omukama, today, is a cultural leader with no governmental functions.

- The Bagisu people

The origin of the Bamasaaba is not known but traditions carried over generationa by oral history point at Egypt (Misiri) as the traditional homeland but this could be the similar epicenter where other migrations from the lower Nile and northwestern Ethiopia took place at the close of the millennium, approximately 900 AD. These groups, also including the Cushitic and Hamitic communities that contstitute the Hima and Tutsi peoples of western Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. Indeed it is difficult to place the Bamasaaba among the Uganda communities because they relate to both Ugandan and Kenyan communities. The language architecture is close to the Baganda and Bakonzo of western Uganda while their cultural traits are close to the Hamitic groups of northwestern Ethiopia. The Bagisu, alternately referred to as Gisu, Bamasaaba, (people of Bugisu region) are closely related to the Babukusu people of Kenya. The Babukusu of western Kenya are believed to have migrated from the Bamasaaba, particularly from areas around Bubulo, in the current Manafwa District. Many clans among the Babukusu have their origins among the Bamasaaba. Masindi Muliro, once a veteran politician and elder of the Babukusu from Kitale, was form the Bakokho clan, with its base at Sirilwa, near Bumbo in Uganda. Other clans common to both sides include Batiiru Babambo, Batiiru, Baata, and Bakitang'a. There are other clans whose names, however, are only on one side, such as Babichache and Balonja who are mainly among the Babukusu. The common cultural ties are a further indication of close relations among the two sister ethnic groups. During the Constituent Assembly that led to the 1995 Cosntitution of Uganda, Mulongo Simon, a delegate from Bubulo East, introduced Babukusu as one of the ethnic groups, acknowledging the fact that both groups, Bamasaaba and Babukusu are intertwined. Bagisu speak a dialect of the Masaaba language called Lugisu (Bantu language), which is fully understandable by other dialects within the Bamasaaba group, and is also understood by the Babukusu. The term Bamasaaba is sometimes used interchangeably with the term Bagisu, even though the latter is actually a sub-group of the main Bamasaaba group.

Mountain Elgon, known locally known as Masaaba (a vulcano 4'321m), the legendary father of the Bagisu people, has a long history of human occupation. The Bagisu, a Bantu speaking people, were the first settlers on the mountain's western and southwestern slopes. Traditionally agriculturalists, they began cultivating in Mt. Elgon's fertile volcanic soils in the 14th century. They have remained on the mountain's slopes up to the present day and now currently inhabit the Mbale District. They are known throughout East Africa for producing high quality Arabica coffee. About a century after the arrival of the Bagisu, the Kalenjins (a Nilotic-Hamitic group) from the north migrated to Mt. Elgon. Those who settled on the mountain called themselves the Saboat. Later, they split into several distinct groups, including the El Kony clan which roamed the forests and high heath and moorland zones. Another group, the Sebei, settled on the northern slopes of the Ugandan side of Mt. Elgon and are currently concentrated within the Kapchorwa District. Unlike the Bagisu cultivators, the Sebei or Ndorobo, are mainly pastoralists. Today the Sebei have also adapted agricultural practices such as commercial maize and wheat cultivation.

Today, the Bamasaaba inhabit the eastern districts of Sironko, Manafwa, Manjiya and Mbale etc. and western Kenya. They are a mainly agricultural people, farming millet, bananas, vegetables, honey, bamboo and sorghum on smaller holder plots. Maize became popular with the arrival of Europeans in the late 1890s. Traditional resources such as medicinal plants and water, sacred grounds and ancestral folklore, passed on orally to younger generations, all contribute to the inseparable relationship between the people and the mountain. Bamasaaba politics before the arrival of Europeans were organised in a decentralized way but maintained strong clan system that brought them together as a community. They had a strong fighting force of youths, whose pre-occupation was to herd livestock and trained in warfare (warriors). They warded off attacks from neighboring communities such as the Luo, Iteso, Elgon Masaai (Sabot and Sebei). Earlier, when the Masaai were still dominant in the eastern part of Mt Elgon, they were the traditional hotile neighbours. The dual economic activity of both crop and animal husbandry generated a resilient economy that supported their livelyhoods and developed into an indepndent cultural community that endured centuries of hostility.

The advance of the European missioneries in late 1890s, facilitated by Kakungulu, a British Muganda agent, established a base for the British colonial rule in the area. This changed drastically the geo-political settings of the Bamasaaba from then onwards. They put up a futile fight against organized elite Ganda fighters but lost their sovereignty and succumbed to foreign rule. Land pressure during the early decades of colonial rule caused the Bagisu to move northwards, hence hitting the territory of the Sebei people (Nilotic tribe), who had fought against Bagisu dominance for over a century. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) led by Bishop Tucker and assisted by Kakungulu, established British and particularly Anglican system in the area, this is, improved labour, road infrastructure and established administrative units based on the Buganda Kingdom centralized system. Up to its indepndence in 1962, Bamasaaba had had several western educated systems.

The Bamasaaba are famous for their traditional male circumcision ceremonies (Mwaga dance), held every year.This ceremony is an important cultural link between the local people around Mt. Elgon. During the three-day-ceremony of dancing, visiting friends and family, feasting and receiving gifts, preceding by a couple of months of preparations, e.g. bamboo strips being handed down to the candidate by the eldest uncle, on the father's side, to symbolize the responsibility and strength needed to face the challenge of manhood, the candidate is decorated with skins and waves two black and white colobus monkey tails in the air as he is accompanied in the running across villages. A combination of sounds, including the ringing of bells attached to the candidates; fiddles, flutes, and group songs, makes this event memorable to anyone watching. Intricate rhythms are played on different traditional drums of differing pitching, and this creates and often stimulates the dancing of everyone present. The person undergoing circumcision is accompanied in the running across the villages, and at the end of it he must be strong and he is not expected to make noise (scream) during circumcision, as otherwise the family will be too embarrassed. It is of great importance for the candidate to "quiet" stand strong during the circumcision to show that he is capable and ready to become a man. The initiates are admitted into adulthood after this ceremony and are expected to begin their formal contribution to the growth of their respective communities. Unlike the Bagisu, the Sebei also circumcise women.

- The Basoga people

Traditionally, the Basoga society consisted of a number of small kingdoms, and they were not united under a single paramount leader. The community was organised around a number of principles, the most important of which was descent. Descent was traced through male ancestors, leading to the formation of the patrilineage, which included an individual's closest relatives. This group provided guidance and support for each individual and united related homesteads for economic, social, and religious purposes. The women of the household cared for the most common staple foods, this is bananas, millet, cassava, and sweet potatoes. Men generally cared for cash crops, these being coffee, cotton, peanuts, and corn. Lineage membership determined marriage choices, inheritance rights, and obligations to worship the ancestors. An individual usually attempted to improve his economic and social position, which was initially based on lineage membership, by skillfully manipulating patron-client ties within the authority structure of the kingdom. A man's patrons, as much as his lineage relatives, influenced his status in society. Unlike the Kabakas (kings) of the Buganda, Basoga kings are members of a royal clan, selected by a combination of descent and approval by royal elders.

In northern Busoga, near Bunyoro, the royal clan, the Babiito, is believed to be related to the Bito aristocracy in Bunyoro. Some Basoga in this area are convinced that their ancestors are the people of Bunyoro.

- The Bakonzo (Bushman)

The houses are made of a double layer of plaited bamboo filled with clay and roofed with grass or banana thatch, although now more frequently with the ubiquitous African corrugated iron roof. Coffee (more recently some people grow cocoa) has been the main cash crop in the foothills. On the plains it is cotton. With an expanding population, recent economic policies favouring stability have taken hold, and farms are being pushed further and higher into the mountain foothills, with the increasing potential for erosion and environmental damage caused by people's pressure on the land. The Bakonzo usually marry early, the girls at about 13 or 14.

The Batwa - Bambuti people