|

- Catalog (in stock)

- Back-Catalog

- Mail Order

- Online Order

- Sounds

- Instruments

- Projects

- History Face

- ten years 87-97

- Review Face

- our friends

- Albis Face

- Albis - Photos

- Albis Work

- Links

- Home

- Contact

- Profil YouTube

- Overton Network

P & C December 1998

- Face Music / Albi

- last update 03-2018

|

1. Khan Kejegei – heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh), Khaas people – 13:03

2. Taskha Matyr – historical story (kip-chookh), Khyzyl people – 16:48

3. Aidolai – heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh), Khyzyl people – 40:47

In 2015, Aycharkh Sayn, the current artistic director of the Ensemble Ülger and a prolific storyteller with several epics to his name, took the initiative to revive the authentic performance of Khakas epic storytelling. These lengthy narrative forms – heroic and historical epics (alyptygh nymakh and historical kip-chookh) – are highly appreciated, but got lost in the second half of the twentieth century (see section “Performing arts”: “storytelling”). Through live performances, the members of the ensemble try to bring them back to life in the manner they were being performed between the 1950s and mid-1980s, without adapting form or content for 21st-century audiences. They have mainly collected such traditional narrative forms of the tribes settling in the north.

The pieces on this album provide a snapshot of this adventure. They demonstrate the different ways in which the Khakas major narrative forms were performed in the Khakas North. Here, among the Khyzyl and Khaas people living at the White and Black Üüs Rivers and Lake Shira (Shira and Khyzyllar aimaghy), epic storytelling lasted the longest. All pieces are performed in the Northern Khakas (Khyzyl and Khaas) style. This style, as compared to the Southern Khakas (Saghai) way of performing epics, is characterized by longer and more complex stories, that are richer in imagination, have a more elevated and clearly pronounced language, and are performed with rich, accurate khai, and elaborate chatkhan playing.

Storytellers like Sömön Kadyshev (see Vol II no° 3. Alyp Khan Khys), Pödör Kurbizhekov and Anna Kurbizhekova (this volume, stories no° 2. Taskha Matyr and no° 3. Aidolai) continued this grand tradition into the 1970s. The tradition was then carried on in a more modest form into the 1980s by a few storytellers, among those Boris Kokov (this volume, story no° 1. Khan Kejegei).

Songs

1. Khan Kejegei

|

| Fragment of heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh - 1), Khaas people, as narrated by Boris Varlamovich Kokov, Chookhchyl aaly (Troshkino), Shira aimaghy. From a 1986 recording at the Khakas Radio Archive, Abakan. |

- Mirgen Irgit: voice and narration (khai in küülip style), khazykhtar (rattle of sheep knucklebones), müüs (rattle made of a cow horn), tuighakhtar (horse hoove clapper)

|

The story is narrated in a Khaas language variant, with some Khyzyl words. Mirgen Irgit performs it in chazagh nymakh* style (“story on foot”), reciting the story alternatingly with küülip khai ** and intoned speech, without an accompanying string instrument. He accentuates the narrative by shaking various percussion instruments, in a way similar to Boris Kokov’s chatkhan strumming when he narrated the story.

Boris Varlamovich Kokov (1915–1980s?) started practicing storytelling as an adult, when only few storytellers were left. Well into the 1980s, he roamed the Khyzyl and Khaas villages in Northern Khakassia to perform at death wakes. He represented Khakassia at the ‘First Tuvan Republican Khöömei Festival’ in 1981 with takhpakh - 3 (song with an improvised text) and an epic fragment performed with khai and chatkhan.

One of Boris Kokov’s favourite stories was Khan Kejegei (or Kijegei – “men’s plait”), a heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh - 1) many storytellers had in their repertoire. The epic recounts at length the life and deeds of the mythical hero Kejegei, whose main goal is to fight evil khans who are causing suffering to his people. Underway, Khan Kejegei pursues many adventures.

In the fragment Mirgen Irgit performs here, Khan Kejegei is in search for a bride. To this end, he asks neighbouring khans (local rulers) for their daughter’s hand, for which he is challenged to fight. After long and unsuccessful wrestling, first with Ai Khan (Moon Ruler) and next with Kün Khan (Sun Ruler), Khan Kejegei finally manages to wrestle down [conquer] a third khan, Salar Khan. This way he gains the hand of Salar Khan’s daughter and marries her.

|

- *Chazagh nymakh – “story on foot” – an alyptygh nymakh performed without instrumental accompaniment and without throat singing.

- **Küülip khai - Küülip or küveler means “to buzz”. It sounds an octave higher than kharygha or ulugh chon khai. It is related to the Tuvan khöömei, the Altain khöömöi and the Mongolian khöömii but focuses less on producing a discernible overtone. It is the main style used for alyptygh nymakh (storytelling). It is often just called “khai” because it is the only style that has continued beyond the end of the Soviet period.

|

Mirgen Irgit

|

2. Taskha Matyr

|

| Fragment from a historical story (kip-chookh - 2) with heroic subject as narrated by Pödör Kurbizhekov in 1959; completed with a dirge song from a historical story (kip-chookh syydy) as narrated by his sister Anna Kurbizhekova, both from the Khyzyl people from Naa aal (Ustinkino), Khyzyllar aimaghy. |

- Tülber Pögechi: voice, narration, topchyl-khomys (lute)

|

Brother and sister Pödör (Piotr) Kurbizhekov (1910–1966) and Anna Kurbizhekova (1913– 1990) are among the last great Khakas nymakhchy - 4 (storyteller of alyptygh nymakh - heroic epics). They stem from the legendary Kurbizhekov lineage of storytellers and singers (see also Vol. I, songs no° 4. Körbe ool takhpaghy, no° 5. Khozanakh yry, no° 10. Khal ool yry, no° 14. Kömege köme, and no° 18. Pai ool yry; Vol. III, songs no° 3. Postai Aryghdyng syydy and no° 13. Khangyra khangyr; Vol. IV, song no° 1 Chyrghalygh churtas).

"Khaijyl Körbe Pödör ool (5)", as Pödör Kurbizhekov was known in the region, had an immense repertory of stories and songs at his disposal. He was famous for his exceptional creativity which is attributed to eeler (inherited spirit masters of artistic talent - eeler - 6), who headed and supported him when performing. As an eelig khaijy (khaijy with a spirit master), he could endlessly continue storytelling, taking only short breaks. This way, the performance of an epic could last for a few nights in row. His sister Anna Kurbizhekova, besides being a storyteller, was also a skilful chatkhan player and above all a gifted singer of yr - 7, takhpakh - 3 (song with an improvised text) and dirge songs, many of which are still sung today. Blind since early childhood after a smallpox epidemic hit the village, she absorbed all storytelling and singing she heard around, and taught herself to play on Pödör’s chatkhan that lay around at home. She was in particular valued for the richness of her songs, and her bright, warm voice.

Tülber Pögechi performs a small fragment – the tragic final part – of Pödör Kurbizhekov’s kip-chookh ‘Taskha Matyr’, a major and cherished story that recounts a major episode in Khakas history: the last war against Mongolian rule – a war that was to become decisive for the destiny of the Khakas people. |

| |

Taskha Matyr (Owl Warrior) is the highest-ranking and favoured warrior in the army of Öjeng Pig, the legendary last leader of the Khakas people (late 17th century). Öjeng Pig leaves for Mool-chiri (Mongolia) with his army in order to wage war against Mool Khan, the Mongol overlord who for years has been imposing irredeemably high taxes on the Khakas people. Among his warriors is also Öjeng’s only surviving son. In the fragment, the Khakas army is completely defeated in a surprise attack. Only one warrior survives, Ölbezek Matyr (Immortal Warrior), who returns to the homeland to deliver the bad news to Postai Arygh, Öjeng Pig’s wife and a daughter of Mool Khan. Postai Arygh leaves for the battlefield to witness it with her own eyes and finds all dead. She starts bewailing her killed husband, her only son, and Öjeng Pig’s beloved warrior Taskha Matyr, with this lament:

Chorba töbin chör pariza / Chobalbin chorchang akh khaltar.

Chobaghlyghlaryng köp chadybysty / Nogha turbadyng, Öjeng Pig?

When trotting down the Erbe river / the bay horse with whitish markings does not beat the road.

Many of your exhausted comrades fell. / Why didn’t you stay upright, Öjeng Pig? …

Postai Arygh decides not to return to the land of her husband, but to stay in her homeland, Mool-chiri, to be close to the bones of her deceased beloved ones. Due to the grave consequences this historical defeat had for the Khakas people, as the tragic death of Öjeng Pig eventually led to Khakassia’s final subjection to foreign rule and its incorporation in Russia, Postai Arygh’s grief has been handed down as a dirge song (kip-chookh syydy) in a multitude of versions.

Tülber Pögechi performs a version by Anna Kurbizhekova (see also Vol. III, song no° 3. Postai Aryghdyng syydy). She narrates the story in the Khyzyl language variant, with intoned speech intersected with sung phrases when warriors address and talk to each another, and with instrumental interludes on the topchyl-khomys. She concludes the story with an extensive dirge song, ‘Postai Aryghdyng syydy’ (Postai Arygh’s grief)

.

|

Tülber Pögechi

|

3. Aidolai

|

| Fragment of a heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh - 1), Khyzyl people, as narrated by Pödör (Piotr) Kurbizhekov, Naa aal (Ustinkino), Khyzyllar aimaghy. From a recording at the Khakas Radio Archive, Abakan. |

| - Aycharkh Sayn: voice and narration (khai in küülip style), chatkhan (wooden box zither)

|

Aycharkh Sayn belongs to a small new generation of epic singers in the Saian-Altai region who are driven by spirit vocation, who are endowed with supernatural inspiration and endurance for storytelling by a spiritual source.

He is able to recite night-long epics impromptu, both his own ones (see Vol III song no ° 2. Toghys khulas sunu küreng attygh Siber Chyltys), as well as those of his predecessors (see also Vol II song no° 3. Alyp Khan Khys). He is one of the most creative musicians, and by far the most expressive powerful one.

Here, Aycharkh Sayn performs a large section of Khaijyl Körbe Pödör ool’s (Piotr Kurbizhekov’s) alyptygh nymakh ‘Aidolai’, a long narrative poem that recounts the journeys and adventures of the mythical hero Aidolai. Aycharkh uses Pödör’s Khyzyl dialect and the typical style thereof in this heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh - 1). The epic with certainty was performed in the 19th century, and it was handed down into the 20th century in almost unaltered form. Aycharkh chose this epic precisely because of this archaic nature in both structure and content.

Aidolai (Full Moon) is one of the Khakas primordial ancestors. Born of supernatural origin and endowed with extraordinary physical, mental and miraculous powers, Aidolai is destined to protect his people, herd and homeland against both human enemies and forces from the underworld, with the help of protector animals, kindred heroes with magical powers, and heavenly forces. In the fragment Aycharkh Sayn renders here, Aidolai is searching for his niece Khan Chaajakh (Ruler Bow), a heroine destined to rescue him in times of severe danger. Khan Chaajakh is enjoying life, roaming the region in a drunken state, singing loudly on her white-winged horse on her way from cheerful company to company. Aidolai does not find her right away, but meets his nephew, hero Timir Khanat (Iron Wing). The two heroes arrive at a large palace where a huge number of guests – sixty heroes! – has gathered, eating and socialising around a large, round table. They are warmly welcomed and accepted in the lively, aristocratic company. Then the host of the palace, Ai Charykh Khan (Ruler Moonshine), opens the conversation: “Who are you? Where do you come from? Who are your parents?”. Thus starts a long exchange of experiences, and Aidolai gets from one adventure to the next.

‘Khaijyl Körbe Pödör ool’ narrated this epic in attygh nymakh style (“story with a horse”, “mounted” - 8) performing it with küülip khai, accompanied by chatkhan, in alternation with unaccompanied intoned speech. From time to time he interrupted the story with an instrumental interlude, or peppered it with a saying, well-wishing poetry, or song. Aycharkh maintains a Khaijyl Pödör’s Khyzyl language variant and his attygh nymakh style (8). Audible in a few places is an unusual, almost enchanting, recitative – a trait Aycharkh did not encounter in any other epic, and which he attributes to the epic’s archaicness. |

Aycharkh Sayn

|

Glossary

- (1) Alyptygh nymakh – heroic epics and heroic sagas; these represent the national cultural heritage of the Khakas people; they are recited using khai (throat singing) and in accompaniment of melodies (kögler) played on the chatkhan (wooden box zither) or the khomys (lute)

- (2) Kip-chhook – this term designates many different kinds of stories, from real as well as fictive stories: their own history (chookh-tar), sad and tragic (mong-lar), true (syn chookh-tar) and fictive (taima chookh-tar) stories as well as anecdotes (khongaldjos-tar). Kip-chookh are performed in prosaic form, never being accompanied by khai singing (throat singing) or instruments. Stories and tales are interwoven with religious concepts, practics and holy sites thereof. There is also given information on the origin and ancestors of the tribes (sööks), their leaders and heroic deeds, and on the creation tales.

- (3) Takhpakh – a song with an improvised text, and saryn or yr, a song with set text and melody. With these songs, performed solo, performers can freely express themselves, sometimes to the accompaniment of a string instrument. Takhpakh are spontaneously improvised texts and give a description of the surrounding nature, one’s home country, a gathering or meeting, or another singer. Takhpakh singers show their talent in special singing contests called aitys. In such competitions two singers alternately compete with constantly improvised verses on a limited number of melodies, trying to outdo each other in originality and wit. Such singers are supported by their spirit owner, who gives them the ability to perform such inspired texts. Set songs are called yr (Khaas, Khyzyl and Khoibal) or saryn (Saghai and Piltir), having more verses, an elaborated theme, and often more distinguished melodies. The majority of these songs are lyric songs, into which the performer integrates own thoughts and feelings about life and past events; some are work, game, or dirge songs.

- (4) Nymakh – general designation of an epic, wherein there is normally designated a heroic epic (alyptygh nymakh).

- (5) Khaijyl – Bards – Kaichi (Khaigee – Khaijy) - are singers, who perform myths, sagas, legends and epics. They belong to the important conservators of this culture. Stories and tales are interwoven with religious concepts, practices and holy sites thereof. There is also given information on the origin and ancestors of the tribes (sööks), their leaders and heroic deeds, and on the creation tales. Such epics have been orally transmitted from one generation to the next one; the whole would fill up about 4,000 pages in books. Several epics are now existent in written form, such as: Altyn-Arygh, Ai-Mergen, Khan-Mergen, Khuban-Arygh.

Such as Ülgen, Geser (creator) or Aru-tös (ancestors) of Turkic speaking and Mongolian tribal communities. They are also called Kaichi, “the people of wisdom“ – “neme bilerkizhi“. Such epics have been orally transmitted from one generation to the next one; such as, e.g., "Altaibuchai", "Maadai-kara" and other tales of the Altaians, which are now existent in written form. Attygh nymakh– (“story with a horse”) – an alyptygh nymakh performed with khai and a string instrument.

- (6) Eeler – Canonical - Töster - texts for addressing all sorts of spirits may be alghys, in order to appease owner spirits (eeler); there are used and recited alghys-tar by alghyschy or shamans in the course of bigger community meetings and gathering such as tagh taiygh (mountain ritual) and tigir taiygh (sky ritual). Alghys is also used to instruct and command the helping spirits (töster). However, before it is possible to direct the helping spirits (töster), these have to be asked to appear by way of special verses, the tös tartkhany (“invocation of helping spirits“).

- (7) Saryn and Yr – are multi-verse songs with a more or less fixed (canonized) text and often a more elaborate melody than takhpakh (song with an improvised text). The northern Khakas tribes call it “yr”, the southern ones “saryn”.

- (8) Attygh Nymakh – (“story with a horse”) – an alyptygh nymakh performed with khai and a string instrument.

- See more information in Worldview, ceremonies and rituals, Performing arts and Traditional vocal techniques. |

| - See more information in the web under: Traditional music and instruments of the Mongolian people – Traditional Instruments of the Khakas and Altai people – Traditional vocal technique of the Khakas and Altai people. |

Ensemble

The ensemble Ülger from Abakan in the Republic of Khakassia was founded in 1989. They have committed themselves to revive and keep alive their tradition in music as well as dance. Ülger means “Pleiades”, the winter stars that rise in early autumn and announce the long, dark, cold season. Legend has it that Ülger rides through the sky on a two-headed horse, scattering extreme cold and snowfall on earth. People believed the Pleiades to be the place of residence of powerful heavenly beings who decided upon a human being’s fate.

|

The Pleiades: The Mushins plays an important role in the Buryat-Mongolian cosmology. Already in earliest times, people believed that the Tenger (powerful heavenly creatures) of the western direction meet at the Pleiades in order to discuss how to help mankind in fighting death and diseases. In this gathering, they created the Eagle, the first shaman. The Pleiades - Mushins also plays an important role in the epic Geser and the creator Ülgen of the Altai population. |

The Khakas people have been known for their rich storytelling traditions, both in epics with throat singing as well as prose, just like their neighbouring Turkic tribes. Songs and stories are often performed in accompaniment of the lute or the wooden box zither. Besides storytelling, they had a wide range of songs for ceremonies, rituals, which lead the people through their life from birth to death, as well as songs for the various seasons. The Khakas also have a limited repertory of pure instrumental pieces and various ceremonial dances. In the evenings or during the long winter nights men as well as women used to gather and entertain therewith. They have attempted to copy the sounds of nature as well as those created when people are working. Hunters and breeders used animal sounds to call or attract their flocks. The oral transmission of their traditions was lost due to forced Russification and the modernization of folklore. Seasonal rituals, clan meetings and shaman sessions were prohibited or firmly discouraged, such as ritual performances at holy sites. Life cycle events like weddings, birth or death, ceremonies for infants and small children, death watches or prayers before the hunt have been lost. When Soviet politics loosened in the mid-1980s, most traditional practices had become rare or had disappeared altogether, especially ritual ceremonies, and epic performances of tribal history having historic importance have become neglected. The non-ceremonial music had turned into folkloristic stage music.

Now young musicians seek to revive these traditions. They move away from the Soviet-based reconstructed “folk music” in search for the authentic patterns of their ancestors. They have started to collect repertoire from the few remaining traditional performers in the villages still alive and from archived audio recordings and music manuscripts. They try to revive the past when village elders are visiting, and they further search the scarce historical ethnographic sources of their ancestors. The ensemble wants their repertory to play an important role in the process of revival.

In their repertoire today there are included heroic epics with throat singing and accompanied by the wooden box zither or lute, as well as old songs describing everyday life: at work, at the occasion of weddings, laments, ceremonial and prayer songs addressed at the heavenly owners of the sky, the mountains, the water, fire and other elements. Many songs were handed down with little or no text at all, which is why the ensemble rescues these old melodies from oblivion by creating instrumentals with them, or finding fitting traditional poetry to them. The aim is to conserve cultural traditions and values for a young generation, using the mother tongue.

Since 2003 the ensemble has been performing under the artistic guidance and direction of Aycharkh Sayn – a gifted musician, virtuoso throat singer, multi-instrumentalist and storyteller. The ensemble has participated in festivals and competitions in Russia and abroad. They have performed in Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Switzerland, France, and the United Kingdom. In 2005 Ensemble Ülger performed at the Sayan Ring Festival of Ethnic Music in Siberia, and since 2006 they have been touring the south of France several times, the last time being in 2011, when they performed at the Russian Art Festival in Cannes. In February 2012 they featured at the Russian Maslenitsa Festival in London.

Khakassia and the Khakas people

The Khakas people are a Turkic-speaking minority, who settled in a region of endless steppes and mountain taiga at the upper Yenisei and in the Minusink Basin, at the foot of the Sayan-Altai mountain range in southern Siberia. Their Turkic-speaking neighbours are the Tuvans, Altaians and Shor people.

In the 17th century A.D. a part of the tribes migrated to the Tien Shan, thereby forming today’s Kyrgyzstan. The migrated Kirghiz have left behind a rich culture as well as an old runic writing.

In the Orkhon Inscriptions dating from the 8th century A.D., there are described the bloody wars and fights taking place in the 6th century against the tribes of the Göktürks, Xueyantuo and the Uighurs in the Han period. There are still songs from the time of this war for autonomy reminding and remembering these conflicts. Petroglyphs, tombs, ritual sites and deer stones tell of days and tribes long gone, which have all settled there from the 3rd century B.C. on, as has been proven by archaeological findings.

Those who remained settled where they live today, in the plains and steppes west of the river Yenisei, upstream in the mountain taiga and in the valley of the Abakan and its tributaries. In 1707, after strong resistance, the land was annexed by the Russian Empire. Songs recalling episodes from this struggle for autonomy have been sung to this very day. In 1923 the country came under Soviet rule, until in 1992 it got the status of an autonomous republic within the Russian Federation.

In today’s Khakassia, various ethnical groups settled between the 6th and the 13th century.

The Khakas tribes themselves were conglomerate of such mixed ethnic groups. In this area, there also settled Kets (the Khanty people) and the Nenets people (Samoyeds) belonging to the tribes of the Uralic group and speaking a Finno-Ugrian language. They formed tribal communities and for a long time were vassals of various Turkic speaking confederations (Dzungars, Oirat Alliance), among those also the Khirgiz and a Manchu-Chinese Qing Dynasty. In the early Soviet period they were restructured as “Khakas”, but they call themselves “Tadar”, with people mainly adhering to their lineage (family name) and clan (söök). In the North of today’s Khakassia there live the Khyzyl people, in the central part the Khaas people. The steppe Khakas (Khaas and Khyzyl) traditionally were pastoralists who moved from winter to summer pastures and supplemented their diet with hunting and agriculture. In the south, there were the Taiga tribes, the Saghai, Khoibal, and Piltir people, who were fishermen, hunters and gatherers, living on agriculture.

Worldview, ceremonies and rituals

The Khakas universe consists of three worlds: the upper world with Khudai or Khan Tigir (“Ruler Sky“) and other spirits having supernatural powers; the underworld with Erlik, the ruler over the evil powers, and the middle world in which we live together with a wide range of spirits, of which the mountains spirits have the greatest impact on human life. People believed to be under the rule of supernatural powers, which they had to subordinate to and which they had to offer sacrifices to. This constitutes an animist worldview (animism – magical belief, religion - all human beings, animals and elements in nature have a soul – a ghost having differing meanings and differing characters). In the elements (fire, water, wind), the spirits have found their homes, furthermore in rocks, trees, mountains and at very particular sites. The belief in nature and to be in compliance therewith, these are two very important matters, which is also visible in texts. Animals live in societies parallel to the human one. Animals and human beings can enter each other’s world and even - temporarily or permanently - change shape.

After death people leave for the “other world“, returning to their relatives who reside in either the ancestral mountain or somewhere in the North. Spirits, who have not succeeded in setting over, will return as evil spirits.

The year is marked by spring, summer, and autumn ceremonies and rituals. The year (chyl pazy) begins in March, with the spring equinox, this constituting the beginning of spring. During the chyl pazy ceremonies the dark, cold season is bid farewell and the warm season met with prayers and coloured ribbons (chalama) that are tied to the sacred birch (pai khazyng) in prayers for a fruitful year. In June, the celebration of the first mare’s milk (tun pairam) is celebrated with riding, wrestling, archery and singing contests. In autumn nature is given thanks for a prosperous spring. Formerly also the return of migrating birds was celebrated in spring. As is known from text findings, migrating birds seemed to have been an important topic for nomads in Siberia and Central Asia. In multi-annual cycles, there were performed extraordinary sacrifice rituals for the spirits of the sky, the mountain or the water.

The spirit owner of nature (eeler) and in particular the spirit owner of the mountains (tagh eezî) are frequently addressed, in personal everyday prayers to show respect and maintain good relationships, and in community invocations and prayers to request the well-being of humans and animals. For misfortune, illness, and catastrophes a range of ritual specialists are invited who mediate between mankind and spirit world. They have helping spirits (töster), mostly in animal shape, whom they ask for help in order to influence the spirit world. Important ritual specialists are the shaman (kham), healer (imchi), and ritual cleaner (alaschy).

Ceremonial and ritual poetry is sung or recited with intoned speech or with overtone singing. Thanks, well-wishing and wish-praying poetry is used for many occasions in order to communicate in sessions and by way of praising words with the helping spirits. Therein these were asked to appear and help in order to manipulate the powers. The Khakas people do not know any praise songs (maktal) such as other Turkic tribes or the Mongols, through which the people may praise other persons, their home country, mountains, and so on using well-wished texts.

Alghys is performed to protect newborn children, a newly-wed couple, the family, community, and animals. Local spirits were also called for help, for protection, for a successful harvest, when entering new land or before hunting. Today, these are also sung as lyric songs. Invocations to the main spirit owners of nature were used to invoke and pray to the spirit owners of sky, mountains, water and taiga. Shamans and healers attempt to get the attention of their helping spirits with invocations and prayers and ask them to help in a session. In order to attract spirits, the people used whispered words and prayers, but also in addition whistling, shouting, moaning, exclaiming, animal imitations, reciting texts or singing songs and, in addition, frequently in accompaniment of a frame drum.

Performing arts

The Khakas people have a rich tradition in storytelling, performing epics in poetry and in prose, proverbs, sayings, wise phrases and riddles, fixed and improvised songs, dirges and laments, wedding songs, lullabies, working songs and game songs.

Text always prevails over music. These linguistic tools are means to tell or sing stories in a convincing and persuasive way. Poetry does have the power to enchant the audience, and for this reason it is performed according to fixed rules. Contextually, poetry is formed on observations regarding parallelism between human experience and natural surroundings.

The Mongols also know songs that are existent in verse form, without any refrain proper, with full vocal power and in the highest register. The melody is surrounded by a “coat“; there is sung a range of more than three octaves; the Khakas songs, however, are rather limited, covering frequently only one octave, with that of the Saghais restricted frequently to only one fifth. These songs are always subject to rather strict rules of presentation and performance. The form is quatrains, and the beginning of every single line is determined by the same vowel of the first word. Texts are adopted by other singers, and there are added some new improvisations: in this way, long stories (songs) are generated and created. The Mongolian people definitely sing these long songs when they are out alone in the steppe and only riding rather slowly. The repertory is a symbol of the freedom and the vastness of the Mongolian steppes and also accompanies cyclic rites of the year and ceremonies of everyday life. Long songs are also an integral part of festivities taking place in the round tents. Among the Khakas, however, such songs are not very common, it is further prohibited to sing in the open steppes or in the taiga, as this might attract the evil spirits. The Khakas also do not distinguish between long and short songs. For rites, there are used alghys (prayers, blessings, thanks), and in gatherings and meetings there are performed alghys and takhpakh (improvised songs).

In the Khakas society creativity has a supernatural source; it is conveyed in the dreams of the people. Such gifts and talents are not only handed down in a line (family), but they may also be awarded to individual persons. Due to the gifts provided by the owner spirits, man and woman are gifted. Skilled story tellers of epics (nymakh), as well as singers singing improvised songs, are supported in their performances by the owner spirits.

Every man and woman can be awarded the gift of creativity by a spirit. Skilled and gifted storytellers of epics and singers of improvised song (takhpakh) are supported during their performances by the spirit owners of nymakh, khai, or takhpakh. They receive instructions and inspiration in their dreams, and are inspired and supported while performing.

Songs were performed at all events where people met spontaneously or on organization, but especially at festive family gatherings and singing contests. People were allowed to sing at day and night, but only in and around the house and the village. For this reason, the Khakas, as opposed to the Tuvin, Altaian and Mongolian people, did not sing songs when travelling or riding the horse across the steppes. Singing in steppe, taiga and mountains is prohibited because it attracts evil spirits. The Khakas people therefore, unlike the Tuvans and Mongolians, do not have travel songs. Most songs can be performed by men and women alike, except for the songs that belong to gender-specific activities, such as (lullabies) cradle songs and work songs. In general, however, songs without throat singing are mainly performed by women, whereas epic storytelling using throat singing is more or less limited to men.

Some songs are integral part of specific occasions like family festivities and year-cycle ceremonies. Blessings (alghys) were recited or sung for welcoming and leave-taking. Love songs, courting songs as well as confirmation of marriage and dowry negotiations formed a rather impressive repertoire. In the context of death, various kinds of dirge (syyt) are sung. In the first year after death ritual dirges are performed: söök syydy (“lament over the corpse”) before and during the funeral and ibirig syydy (“lament at a post-funeral wake”) at the wake, to see off the souls of the deceased and thus ease the passage of the deceased into the other world. Later, people sing non-ritual dirges at home in order to commemorate the beloved.

The Khakas people have also songs that are not bound to specific occasions: takhpakh, a song with an improvised text, and saryn or yr, a song with set text and melody. With these songs, performed solo, performers can freely express themselves, sometimes to the accompaniment of a string instrument. Takhpakh are spontaneously improvised texts and give a description of the surrounding nature, one’s home country, a gathering or meeting, or another singer. Takhpakh singers show their talent in special singing contests called aitys. In such competitions two singers alternately compete with constantly improvised verses on a limited number of melodies, and try to outdo each other in originality and wit. Such singers are supported by their spirit owner, who gives them the ability to perform such inspired texts. Set songs are called yr (Khaas, Khyzyl and Khoibal) or saryn (Saghai and Piltir), having more verses, an elaborated theme, and often more distinguished melodies. The majority of these songs are lyric songs, into which the performer integrates own thoughts and feelings about life and past events; some are work, game, or dirge songs.

The repertoire comprises a small group of dirge songs or laments (syyt) that are designated as lyric songs; dirge songs are ritual songs; laments having improvised texts are performed by a singer and tell of the person deceased and those he has left behind. Personal laments may be taken over by other singers, thus being slowly integrated into the common song repertoire.

Other dirge songs stem from epics or stories (kip-chookh) and constitute the oldest surviving form of the Khakas folklore. Laments are complaints about one’s misfortune, misery or suppression and are also often called “yr” ("song"). These laments are often sung by animals or human beings who have turned into animals and who sing about their harsh living conditions or unfair treatment - another display of the parallels to suppression and the life as vassals shared by the people.

The most prominent Khakas storytelling tradition is epic stories (“epic with a hero”) performed by specialized storytellers at meetings and gatherings during long winter nights – also to accompany souls into other worlds, or before hunting to please the spirit owner of the animal to be given the permission to shoot deer. Performance with throat singing and the box zither or lute was reserved for male performers and called “epic with a horse”. Unaccompanied recitals, being performed with intoned speech voice, are called “epic on foot” and may also be performed by women. An “epic on horse” sets off with an instrumental prelude. Then the storyteller tells the story alternating with throat singing and with repeated text having temporary shifts to a higher or lower tone and with unaccompanied intoned speech. The overtones of the throat singing create an extraordinary timbre texture that brings about the supernatural time-space feeling, in which the epic world comes to life. Every now and then the story is suspended with an instrumental interlude, a blessing, well-wishing expressions, songs or laments.

The most talented storytellers are provided with inspiration by their spirit owners and they are called eelîg khaijy (kaichi). They could endlessly sustain their performance. Such a story could last for several nights in a row, being interrupted only by short breaks. The storytelling tradition was continued without any interruption by Khyzyl storytellers until the 1970s. Among the last great ones were Semyon Kadyshev (1885-1977), who lived among the Khaas people near Lake Shira, and brother and sister Pyotr Kurbizhekov (1910-1966) and Anna Kurbizhekova (1930-1990), who lived along the Üüs river.

Prose stories, which are called “kip-chookh”, are told by women as well as men and include sacred myths about the origin of the world, creator spirits, spirit owners and other supernatural spirits; stories and legends about historical heroes, shamans, ancestors of the tribes; as well as humorous tales and fairytales. The most comprehensive kip-chookh stories, just like alyptygh nymakh stories, “epic with a horse”, include songs, dirge songs, and laments.

Epics (stories) and singing were accompanied by string instruments. In this way, the gait of a horse was imitated, or the adventures of a hero were being emphasized. Hunters used various wind instruments to imitate animal calls and thus attract the desired game. When people played flutes, string instruments or the jew’s harp, it was mainly for personal entertainment. They improvised on standard melodies, or they spontaneously created their own melodies, being inspired by the sound of the environment or closer surroundings.

Such rich creativity is awarded by a supernatural source, conveyed in the dreams of the people. Such gifts and talents are handed down in a line (family) and on the basis of their ancestors. Men and women alike are supported by spiritual powers, which are independent but, however, still responsible for the epics performed in throat singing. These spirits protect and support the “khaijy”, the storytellers of epics, and takhpakhchy, the singers of improvised songs.

Traditional vocal techniques

- Khai (throat singing – guttural singing)

Khai (or kai, as it is called among the Altaian and Shor people) is the traditional form of overtone singing from the north-western Sayan-Altai region, with only the highest and lowest vocal registers being used. It is largely a male vocal technique, though women are known to have performed and to perform it as well. It is inextricably linked with heroic storytelling, epics with a hero / heroine; it is in high esteem and constitutes an important part of the cultural heritage.

Throat singing and overtone singing is a common feature of all southern Siberian Turkic, many Mongolian, as well as some Kazakh peoples. It is also performed by many Turkic tribes in Central Asia. Overtone singing is a very special technique, wherein a single vocalist produces simultaneously two distinct tones. In its clearest (Tuvan and Mongolian) form, one tone is a low fundamental pitch that is sustained like a drone, while the second is a series of flutelike harmonics that resonate high above this drone. A real master may amplify the overtones at the expense of the fundamental pitch, even to the point that the drone becomes inaudible. Another technique often used combines a normal glottal pitch with a low-frequency pulse-like vibration, known as vocal fry. Texts are usually sung in such a vocal fry of about 25-20 Hz. The Shor and the Khakas people do not usually sing their texts in such a fundamental pitch, as they use kharygha more sparingly.

Unlike the Tuvans and the Mongolians, the more northern located Khakas, Altai and Shor people do not express the overtones very much in their khai or kai. Khai is produced by generating a fundamental tone while pressing the diaphragm and slightly pressing together the vocal cords. In this way, a hoarse sound arises, accompanied by soft overtones that change with the vowels of the recited text, thus creating a multi-layered sound hovering above the basic drone. Primarily, the epics are performed together with a string instrument. In the Khakas tradition, however, the overtones are rarely used to create a melody. Khai is not used to show virtuosity, but rather to convey texts in a convincing way; for this reason, this is only rarely performed independently. By using the technique of khai, the storyteller clearly emphasised the text, while at the same time making overtones subtly resonate above the recited text. The overtones help to reinforce the story’s text, as they create an extraordinary timbre texture that brings about the supernatural time-space feeling, in which the epic world and the story come to life.

- Kharygha, kharghyra (from khorlirgha, the Khakas word for snoring) or ulugh chon khai (“khai of the respected elders”) is the lowest sound a human voice can generate. This sound is related to the Altaian karkyra and the Tuvan kargyraa. It rises from the deepest part of the trachea and resonates in the chest. It is used for short episodes in heroic epics.

- Küülip or küveler means “humming” and sounds an octave higher than kharygha. It is related to the Altaian köömöi, the Tuvan khöömei, and the Mongolian khöömii, but focuses less on producing discernible overtones. It is the main style for storytelling. This style is often simply called “khai” because it is the only style that has survived the Soviet period.

- Syghyrtyp means “to whistle”. This is a style of overtone singing, wherein there are generated tones in the throat that are comparable with the wailing sounds of the wind. Overtones are created between cavity, pharynx and tongue. This style is related with the sygyt of the Altaian and Tuvan people, wherein the highest and brightest tones are generated as the highest register of the voice is used. (In nature, every single tone and sound has overtones; even the wailing of the wind has its overtone vibrations). Whistling is only sparingly used; it is only used for short melodies at the end of phrases; humming (küülip) is followed by whistling.

The old performers mostly used küülip to perform stories and songs. Performers today use khai (overtone) mainly for songs and, to a smaller extent, for prayers. Kharygha and syghyrtyp are as frequently used as küülip.

|

| - See more information in the web under: Traditional music and instruments of the Mongolian people – Traditional Instruments of the Khakas and Altai people – Traditional vocal technique of the Khakas and Altai people |

|

From left to right: Altyn Tan Ayas, Tagir Asochak, Albi, Lunic Ivanday, Aychark Sayn, Mirgn Irgit and Tülber Pögechi

- from left to right: Lunic Ivanday, Aychark Sayn, Mirgen Irgit, Tülber Pögechi and Altyn Tan Ayas

|

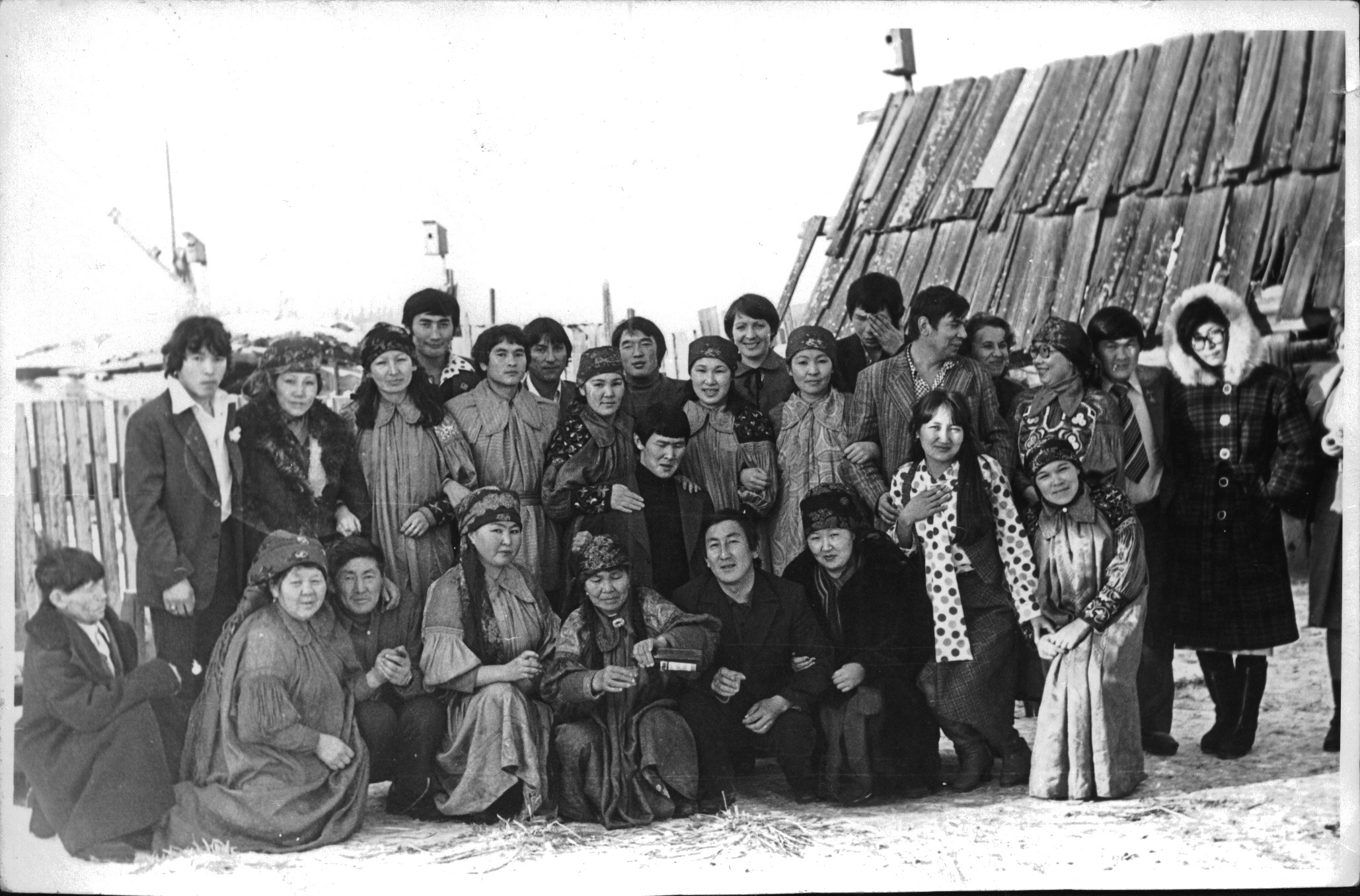

Wedding of relatives of Mirgen Irgit's mother, early 1980s, Arshanar aali (Arshanovo), Altai aimaghy

- wedding in the Borchikov linege, Kirba aal, Pii aimaghy, early1980 - Mirgen Irgit's mother in the far left

|

From left to right: Altyn Tan Ayas, Lunic Ivanday, Albi, Tülber Pögechi, Mirgen Irgit and Tagir Asochak

|

Instruments:

|

|

– aghas-khomys – aghas-khomys

|

- Khomys (string instument)

This is a two-string or three-string lute, related to the Altaian topshur, the Tuvan doshpulur and the Mongolian tovshuur.

The Khakas people play two types of khomys: the aghas-khomys and the topchyl-khomys. Both have a body and neck carved from cedar wood, but while the former has a wooden sounding board from cedar wood, the body of the latter is covered with the skin of wild roe deer, domestic goat, or cattle. The traditional stringing is of twisted horsetail hair, and the strings are tuned a fourth or fifth apart; the three-string khomys is tuned a fourth plus a fifth apart.

– topchyl-khomys – topchyl-khomys

|

|

- Chatkhan or chadyghan (string instrument)

The chatkhan is the most prominent instrument of the Khakas people. It is a plucked long box zither with six to fourteen strings, distantly related to the Tuvan chadagan, Mongolian yatga, Japanese koto, Chinese quin and Korean kayagum.

The Khakas zither is a 1.5 metres long box from spruce wood, with each metal string running over an individual movable bridge made from sheep’s knucklebone. It is likely to originally have consisted of a short body (about 50 cm long) hollowed out from underneath like an upturned trough, with strings of horsetail hair.

However, in the 18th century it already broadly had its present shape: a long box of nailed boards with 6 or 7 metal strings. It has a rather smooth sound, ideal for performance in intimate company. The chatkhan is tuned in a pentatonic scale, with one or two strings tuned a fifth and/or octave below the lowest melody string, to obtain a drone. Some strings are also pressed to the left of the moveable bridge with the left hand, to raise the pitch. The strings are plucked and strummed to the right of the moveable bridges with the right hand to produce both melody and drone. The left hand is used to press particular strings to the left of the moveable bridge. In this way, diatonic melodies can be played on the pentatonic instrument, as well as the adorning gliding tones and vibratos so typical for the instrument.

Unlike the long zithers (yatga) of the Mongols, who mainly used the long zither at court and in monasteries since strings symbolised the twelve levels of the palace hierarchy, the chatkhan was used to accompany lyrical, historical and epic stories and heroic tales in intimate gatherings of common people, especially at weddings and nocturnal death wakes.

The chatkhan (like the Khakas lutes) could hold a spirit, and therefore handling and playing was bound by taboos and rituals.

|

|

- Khazykhtar (percussion instrument)

Rattle of sheep knucklebones. |

|

- Müüs (percussion instrument)

Rattle made of a cow horn; filled with small stones and closed with leather. |

|

- Tuighakhtar - Paddock – hors's hoof (percussion instrument)

Horse hoove clapper. |

|